A Plan for All Londoners?

Interrogating the London Plan through Republication

By Chi Nguyen

Many Londoners won’t know about or have come across the London Plan, but it shapes their lives on a daily basis. It is one of the most crucial documents for our city, and what it contains shapes how London evolves and develops over coming years.

Mayor Sadiq Khan, The London Plan, Draft for Consultation, 2017

The London Plan is an important public document in London, UK’s, planning system, prepared and published by the Mayor of London and the Greater London Authority. It is a policy document used by boroughs and local authorities to administer planning decisions and govern spatial development across Greater London. Building on Mayor Sadiq Khan’s vision of “A City for All Londoners” (2016), the new London Plan provides a strategic framework for how the capital will change over the next twenty to twenty-five years to achieve “good growth,” defined in the plan as development that leads to a more socially integrated and sustainable city. [1] The plan will significantly affect the city’s housing, transportation, environment, and economy, as well as green, social, heritage, and cultural infrastructure. The plan is interested in equality, diversity, and inclusion in the city’s evolution, and seeks “to promote and deliver a better, more inclusive form of growth on behalf of all Londoners.” [2]

Image 1 | Mayor of London, “The London Plan: The Spatial Development Strategy for Greater London.” Draft for public consultation, London: Greater London Authority, 2017

Through an extensive two-year process of public consultation and formal “Examination in Public” reviews of the draft plan beginning in 2017, Londoners were invited to have their say about the city’s proposed transformation. The process aimed to give citizens a meaningful opportunity to take part in shaping London’s future. By inviting citizens to comment on the draft, the publication additionally functioned as a democratic device, a way for the public to join the discussion and share views. Ultimately, the London Plan will serve as a city-wide administrative apparatus for governance, but through its draft review process it was simultaneously intended to facilitate civic participation and public debate.

But, how democratic (and equal, diverse, or inclusive) is the London Plan? To publish means to make public, of the people, and in its broadest sense, open to all. [3] The key word here is “all,” and who and what is implicated by the term. If “all” is taken to mean the whole quantity or widest extent of a particular group or thing, such breadth conceptually ties into the mayor’s ambition to create a city for all Londoners and his “plan to ensure that everyone, regardless of their background or circumstances, is able to share in and make the most of London’s prosperity, culture and economic development.” [4] In taking a closer look at the publication’s form and content, it soon becomes apparent that “all” is complicated and not easily defined, revealing some tensions and contradictions about the London Plan’s publicness and openness. It raises questions about the relationship between making the plan public and making London open to all Londoners.

From the outset, there are concerns about limited audience and access to the review process, a typical problem of public planning initiatives. Given the scale of the city and the scope of this particular plan, these basic hurdles constitute a heightened challenge to a system that relies on citizen participation. [5] Despite the large civic remit, as Mayor Khan candidly notes in the foreword, “many Londoners won’t know about or have come across the London Plan.” [6]

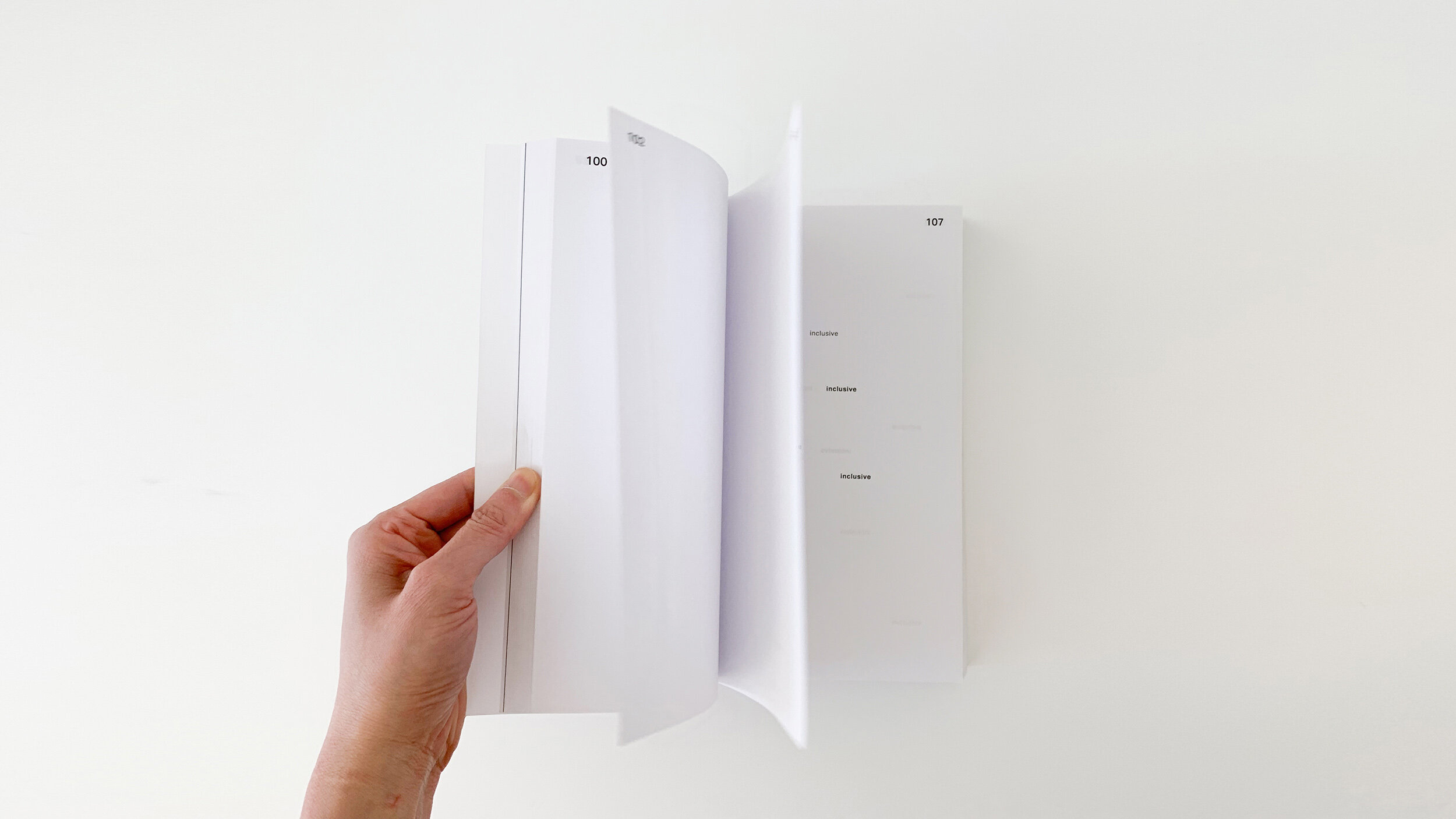

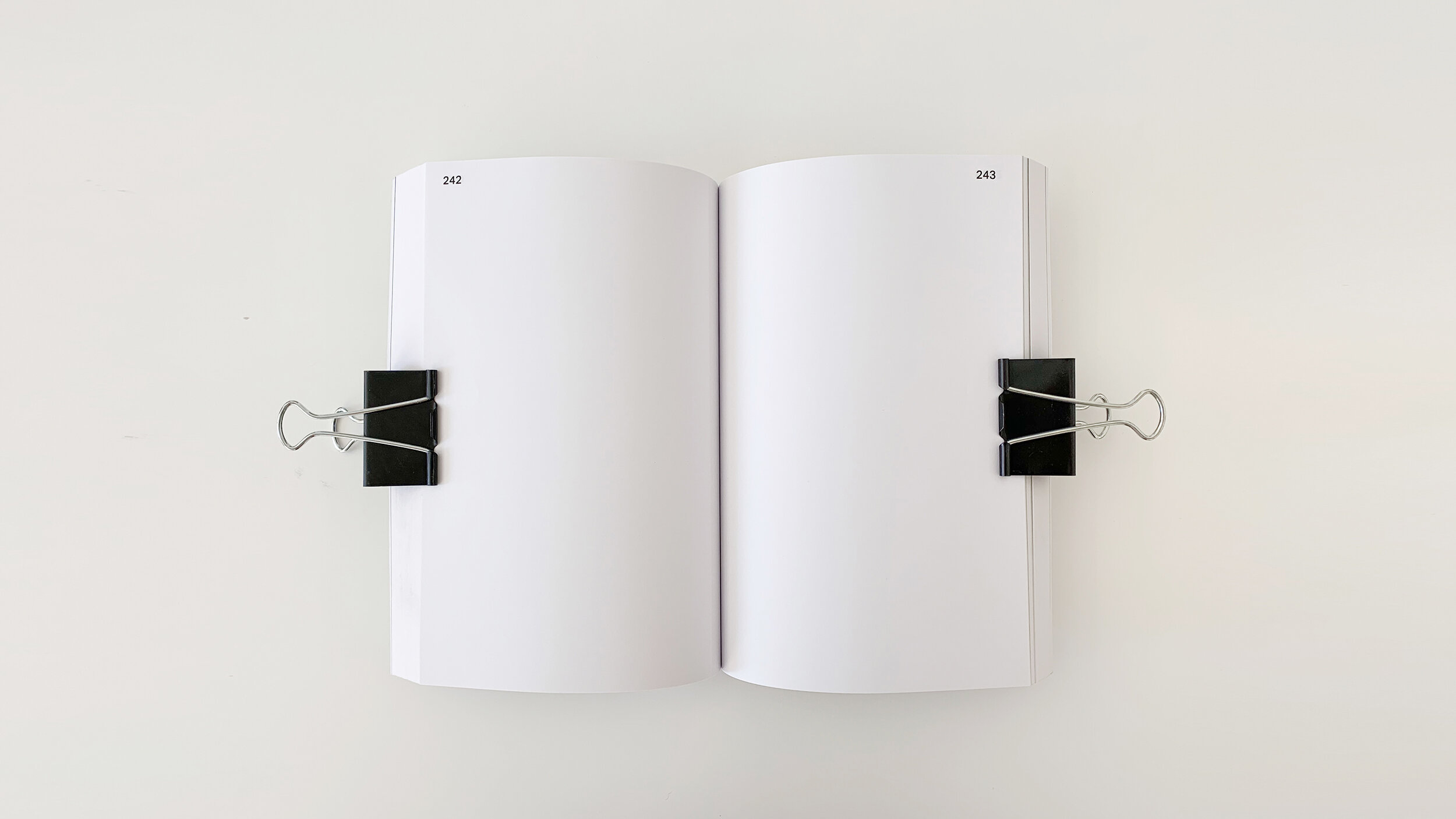

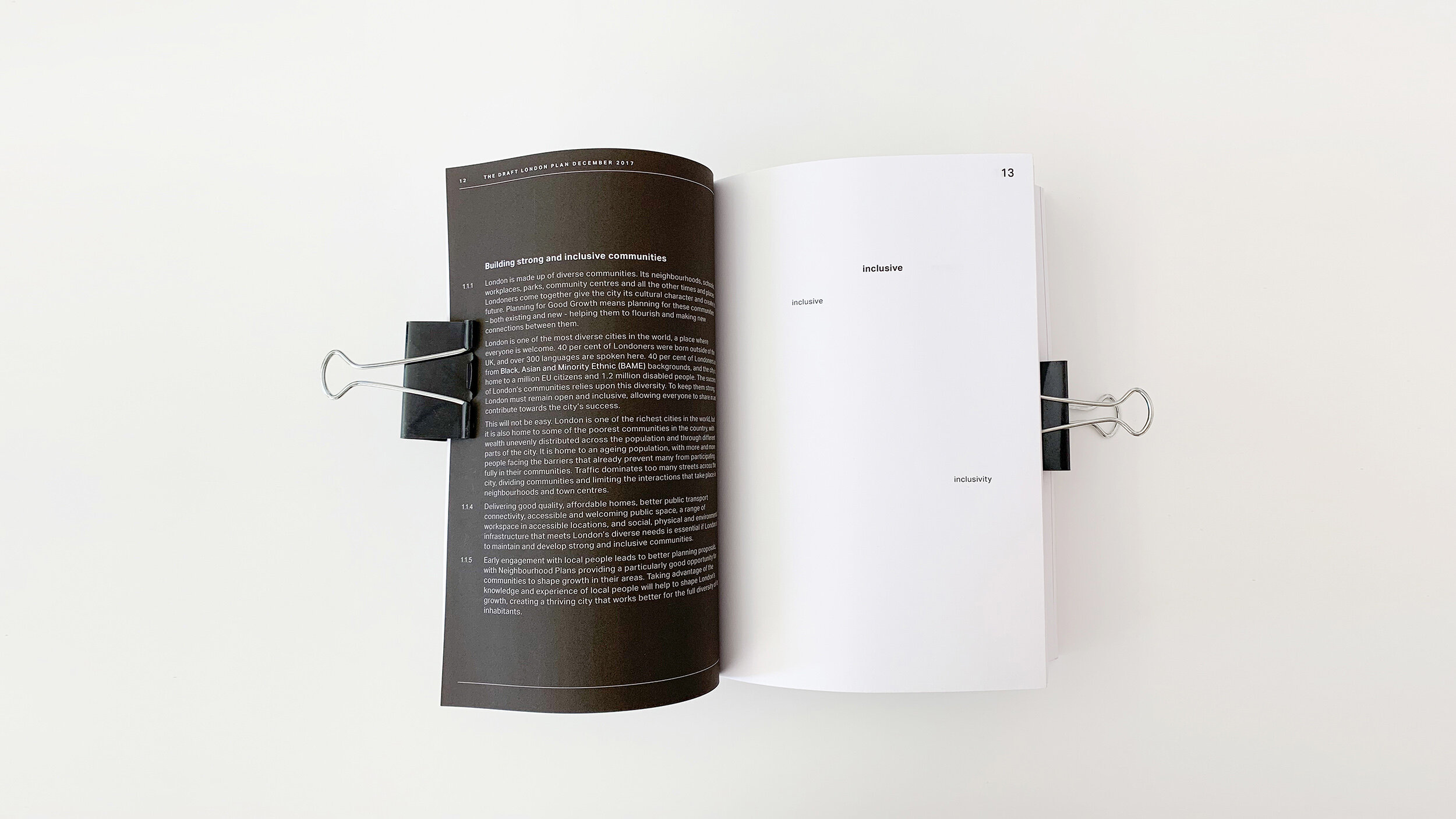

Image 2 | Chi Nguyen, Word Count: The London Plan and the Textually Absent, 2019, 6” x 9”. Visual representation of the inclusion of minority communities within the draft London Plan, highlighting the number of times the terms “inclusive,” “LGBT+,” and “BAME” appear in the text

Few people will have encountered it. On top of such minimal awareness and interaction, engagement is further hampered by the physical reality of the publication. At over 500 pages, the London Plan is heavy in both weight and technical language, not an easy pick-me-up book for public consumption. Rather, it sits somewhere uncomfortably between a corporate vision statement, a reference manual, and a legal textbook. Its digital version, a maze of online links, is likewise dense and just as difficult to navigate.

Even when readers do find a way in, they may not see themselves reflected in the plan. At odds with recurrent statements to build diverse, inclusive communities, the plan is often vague about what and who exactly this constitutes. The terms “all Londoners” and “public” are repeatedly used throughout but no clear definition of either is provided, nor is reference made to whom they include. In much of the text, “Londoners” and “everyone” are equivalent umbrella terms and sometimes interchangeable; the two words frequently accompany each other in the same sentence. Implicitly, all who visit, live, and work in London are being widely addressed. However, considering the plan’s policy rhetoric about developing a fairer and more equal city, [7] there are cases where specificity is necessary—in particular, for those individuals who fall under the protections of the Equality Act of 2010, which states that equality of opportunity must exist between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic (age, disability, gender reassignment, race, religion or belief, sex, sexual orientation, marriage and civil partnership, and pregnancy and maternity) and persons who do not share it. [8] It is a statutory obligation of the mayor to ensure that the plan meets this duty, and that planning’s impact on individuals’ wellbeing has been accounted for.

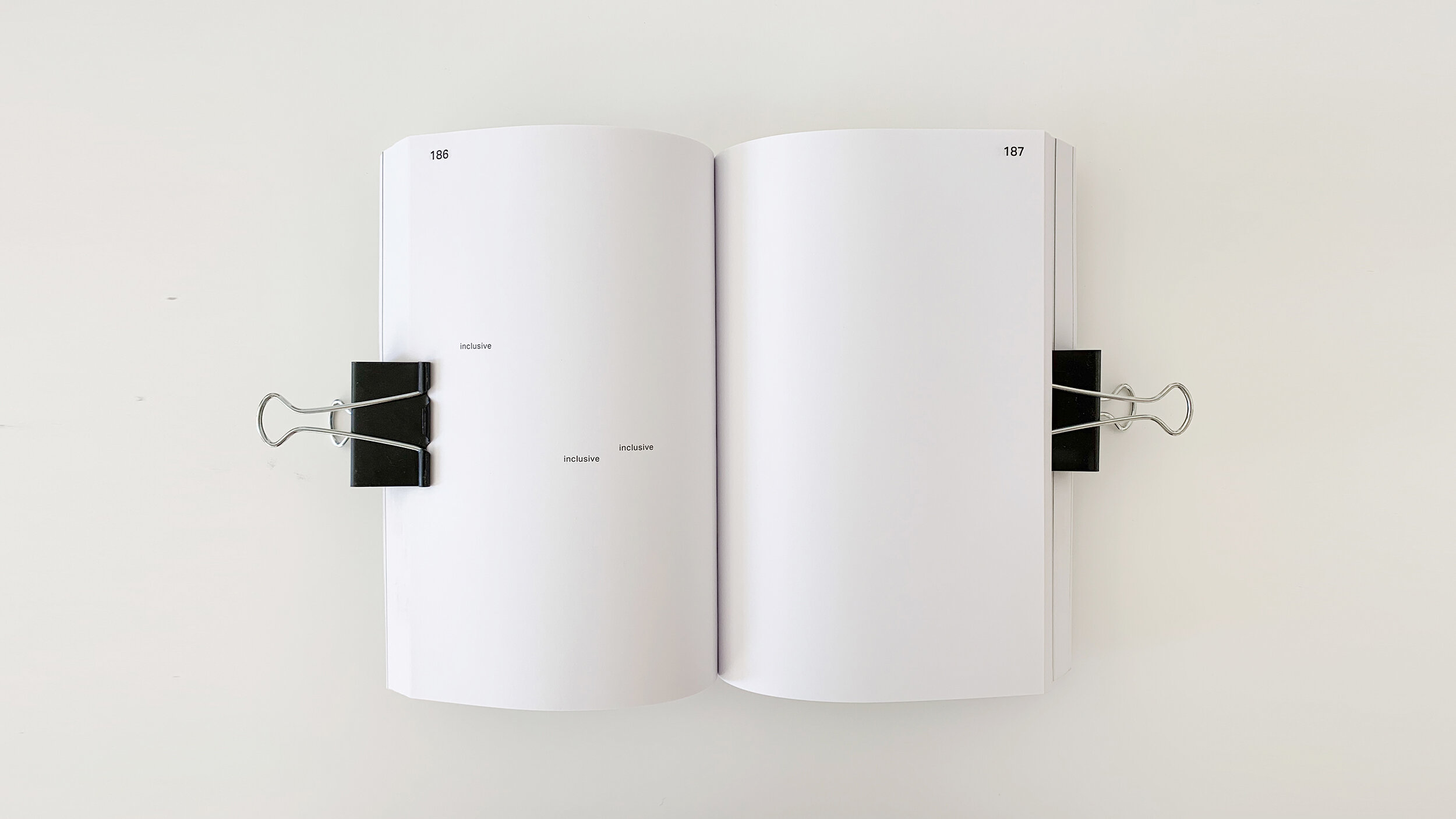

It is striking then that of the five hundred pages in the draft plan, there are over a hundred word mentions of “inclusive” but comparatively few naming the characteristics described in the Equality Act. For instance, only four appearances each of “LGBT+” (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, plus) and “BAME” (black, Asian, and minority ethnic). At a community consultation workshop, the Greater London Authority stated its reasoning for the exclusion as being that, by not explicitly calling attention to any one group, the plan embraces all groups, “all Londoners.” [9] And yet, as the workshop participants pointed out, it is this distinct lack of naming, the absent recognition of the unique needs of, and particular challenges faced by, certain vulnerable groups that can further drive entrenched inequality. [10]

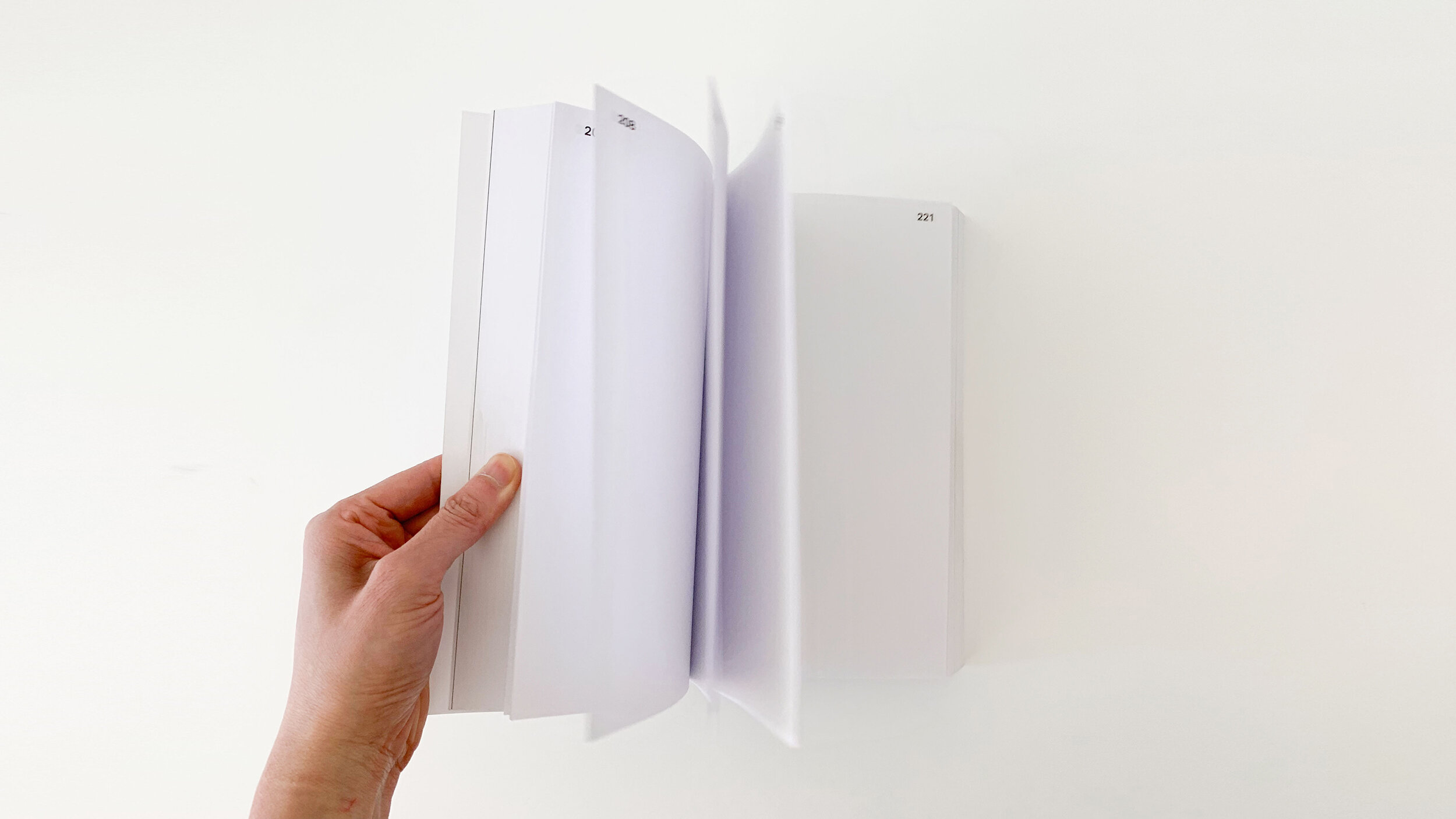

In order to amplify this point and to tangibly demonstrate the disproportionate occurrence of these references, I created the alternative publication Word Count, reproducing the draft London Plan but omitting all text except for the words “inclusive,” “LGBT+,” and “BAME,” the latter two represented by black pages. Retaining the plan’s formatting, what remains is a startlingly white book. A mostly blank copy. Word Count visually highlights how infrequently these communities show up—and how (textually) absent they are—in the plan and by extension, arguably, in the future of London. Through republication, Word Count makes visible the disparity between intention and attention and the communication gap between what is asserted by policymakers and what is actually articulated to the public. It encourages a more critical reading of the plan and consideration of the chosen language and the ways in which, per Marshall McLuhan, the medium carries the message. [11]

By subverting the plan’s physical limitations and textual absences, the republished edition opens up a different avenue to ask about who is or is not included in London’s planning. Exhibited at PhD Research Projects 2019, In Permanent Readiness for the Marvellous at The Bartlett School of Architecture from February 19 to March 5, 2019, and shared via social media, Word Count introduces audiences to the London Plan in a way they may not normally encounter or associate with government documents. Through creative publishing, Word Count widens the public lens through which discussions of what kind of city and future citizens want can be seen. While public processes are complex and nuanced, with many drivers affecting models of engagement, Word Count provides an example of an alternative approach to stimulating public conversations about planning—one that pays close attention to medium, form, and format, and offers a non-traditional entry point for probing city planning texts. It is one way to make the words of the London Plan count.

Image 3-9 | Chi Nguyen, Word Count: The London Plan and the Textually Absent, 2019, 6” x 9”. Visual representation of the inclusion of minority communities within the draft London Plan, highlighting the number of times the terms “inclusive,” “LGBT+,” and “BAME” appear in the text

Notes

1. Sadiq Kahn, Mayor of London, foreword to “The London Plan: The Spatial Development Strategy for Greater London” (draft for public consultation, London: Greater London Authority, 2017), XIV, https://www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/planning/london-plan/new-london-plan.

2. Mayor of London, “The London Plan: The Spatial Development Strategy for Greater London” (draft for public consultation, London: Greater London Authority, 2017), 15; see also: Mayor of London, “A City for All Londoners,” (London: Greater London Authority, 2016), 11, 69–85, https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/city_for_all_londoners_nov_2016.pdf.

3. Paul Soulellis, “Making Public” (public talk, Fondation Galeries Lafayette, Paris, June 2015).

4. Mayor of London, “A City for All Londoners,” 5.

5. Greater London Authority Act, Section 335 (1999), http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1999/29/section/335.

6. Kahn, “The London Plan,” XIII.

7. Mayor of London, “The London Plan,” 3, 13.

8. Equality Act, Section 149 (2010), http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/section/149/data.pdf.

9. UCL Urban Laboratory and Queer Spaces Network, “Queering the London Plan” (workshop, ThoughtWorks, London, February 23, 2018).

10. “Based on Urban Lab’s research [on LGBTQI+ nightlife spaces in London] we would argue that failure to name these specific groups [LGBTQI+ communities] in the last London Plan has contributed to a lack of attention to their needs and spaces, resulting in the loss of 58% of venues over a 10-year period.” UCL Urban Lab, “Draft London Plan LGBTQI+ Community Response” (written statement submitted to the Greater London Authority, March 2, 2018), https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/UCL%20 Urban%20Laboratory%20%282231%29.pdf

11. Marshall McLuhan, “The Medium is the Message” in Understanding Media: the Extensions of Man (New York: MacGraw-Hill, 1964), 1–18; see also: Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore, The Medium is the Massage (New York: Bantam, 1967).

Bio

Chi Nguyen is a graphic designer and PhD candidate at The Bartlett School of Architecture whose practice focuses on the field of architecture and urbanism. The publishing experiment Word Count forms part of her visual research on publishing and publics that looks into the communication design of civic publications. A published writer, she also tutors at Central Saint Martins and The Bartlett, and previously led the communication design work of MacLennan Jaunkalns Miller Architects and Gow Hastings Architects in Toronto.