Between Women

By Em Cheng and Jennifer Davis

Intro by Jennifer Davis

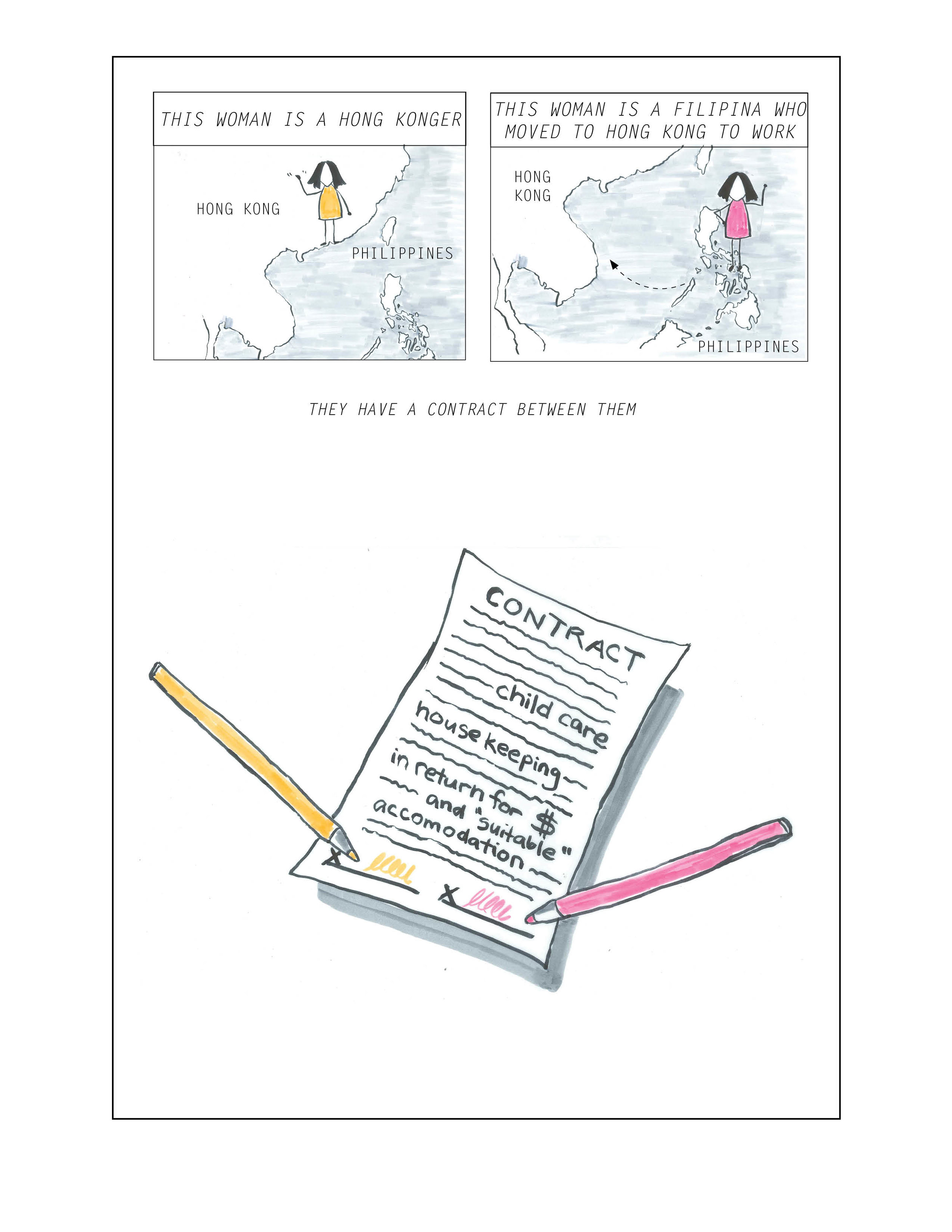

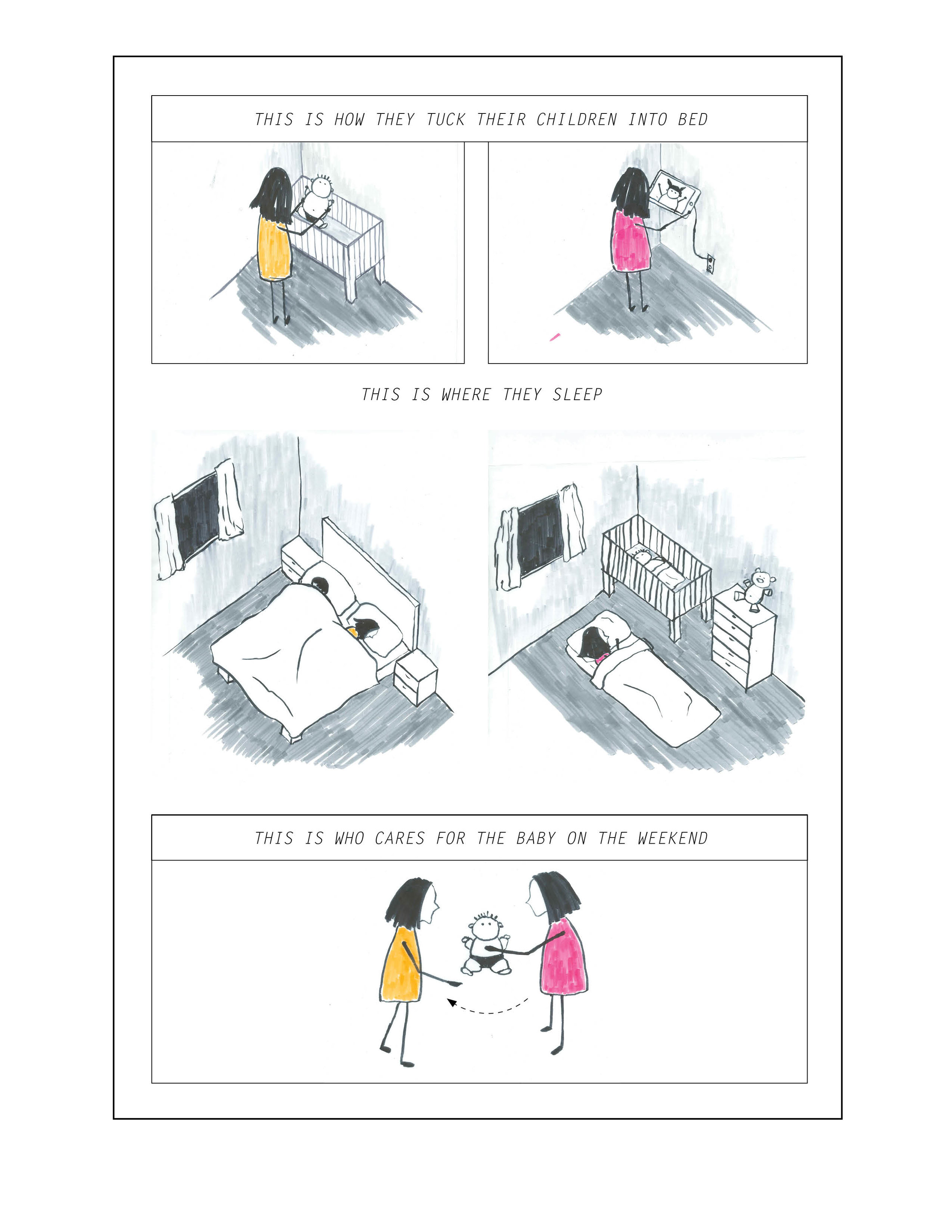

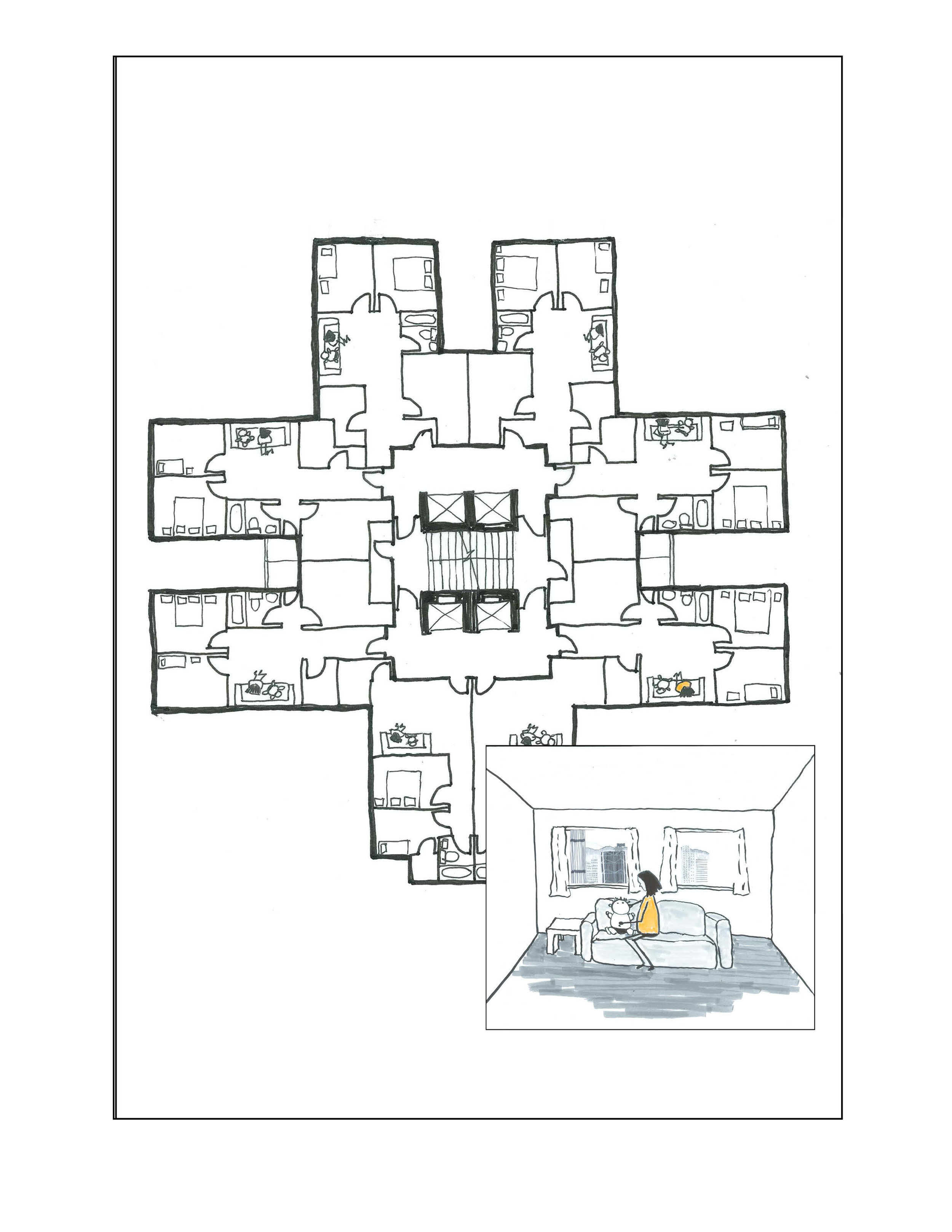

Every day in Hong Kong, pairs of women sit across from each other and sign a version of the same contract. The “Employment Contract for a Domestic Helper Recruited Outside of Hong Kong,” developed by the local Labour Department, outlines duration of employment, wage, duties, and other clauses one might expect. It also clarifies that the workplace is in fact the home of a Hong Kong family whose new employee is a temporary resident who has travelled from the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, Sri Lanka, or another South Asian country to work. The contract goes on to explain that the Migrant Domestic Worker (MDW) must live with her employer’s family, acknowledges the typically small apartment sizes in Hong Kong, then specifies via a yes/no checklist what furniture, bedding, and bathing facilities are available to the worker in her household-cum-workplace. At the micro-scale, two women come to an agreement that resolves their respective responsibilities to provide for and take care of their families in their respective circumstances. But so pervasive is this one-on-one scene that it has, over the past forty years, reshaped Hong Kong’s demographics, labour landscape, and spatial realities. The 300,000-plus Filipino and Indonesian MDWs are the largest visible minority populations in the region and, employed in one of seven households, provide child care and elder care that is integral to the functioning of the broader society and economy while remaining precariously employed.

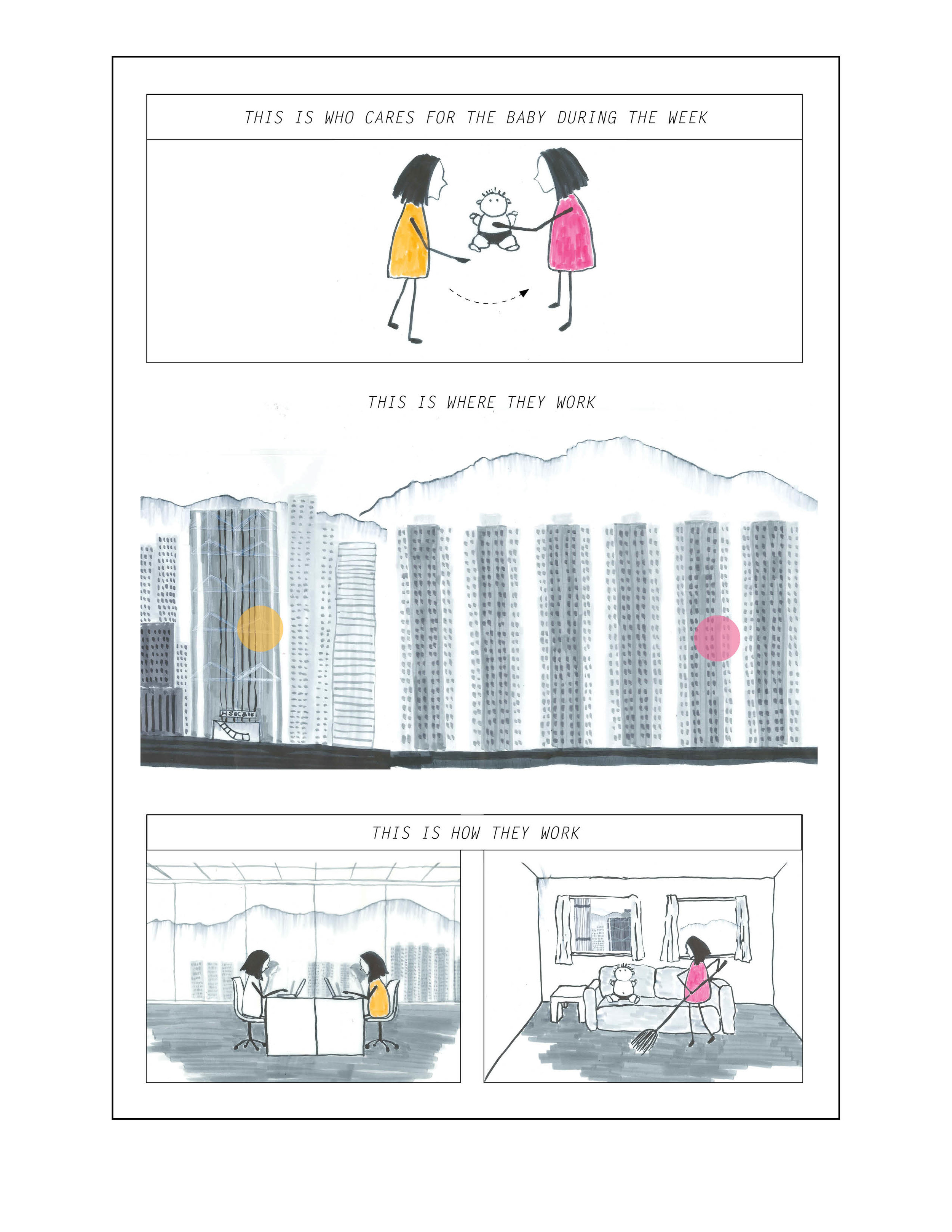

The women in this story have a lot in common—they both have a husband and child, attended university, consider themselves middle class, and employ a domestic worker. Since the early 1970s, their countries’ economies have been interdependent due to key developments in their respective labour markets: a demand for skilled labour in the offices and service-based industries of Hong Kong and a “labour export policy” in the Philippines intended to address the local scarcity of decently salaried jobs. The Hong Kong government’s solution to their labour shortage was to entice women to join the paid workforce. Meanwhile, they promoted the importation of a female workforce to do “women’s work,” taking advantage of the labour surplus in the Philippines rather than providing the financial and spatial infrastructure that would allow domestic care tasks to move outside the home into day-care centres or retirement communities. It is a policy in line both with a laissez-faire economic approach and a desire to maintain a cultural status quo that assigns all reproductive and domestic labour to the women within a household.

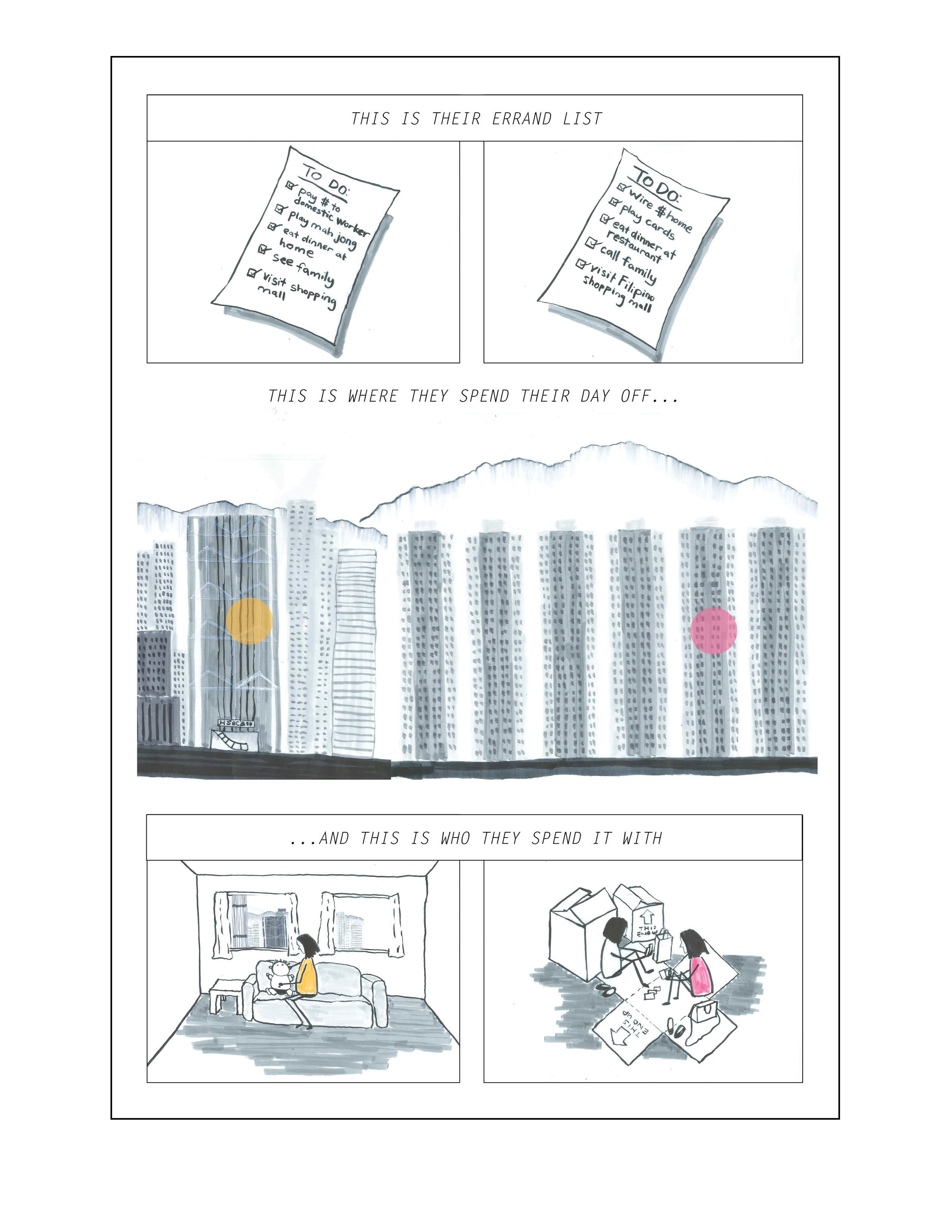

Within this framework, women from South Asia—motivated by the higher pay, career aspirations, sense of adventure, or a mix of all three—make the calculated decision to emigrate to Hong Kong. The story’s two protagonists thus find themselves on the same side of the labour equation that assigns labour along gender lines while adding the expectation of contributing a second household income. In this context, however, their different nationalities and labour statuses are constantly reinforced by how and when they are allowed to occupy urban and domestic spaces throughout the city.

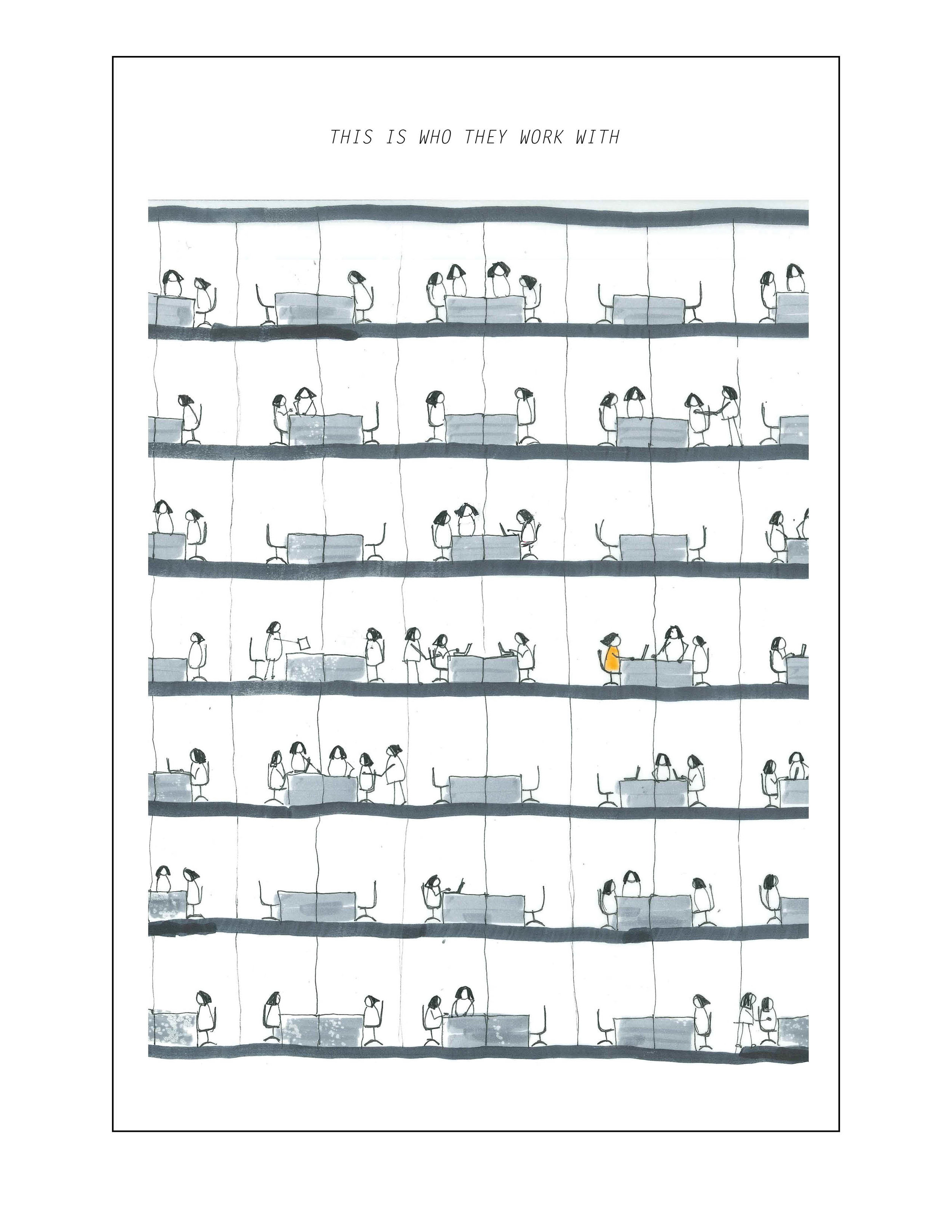

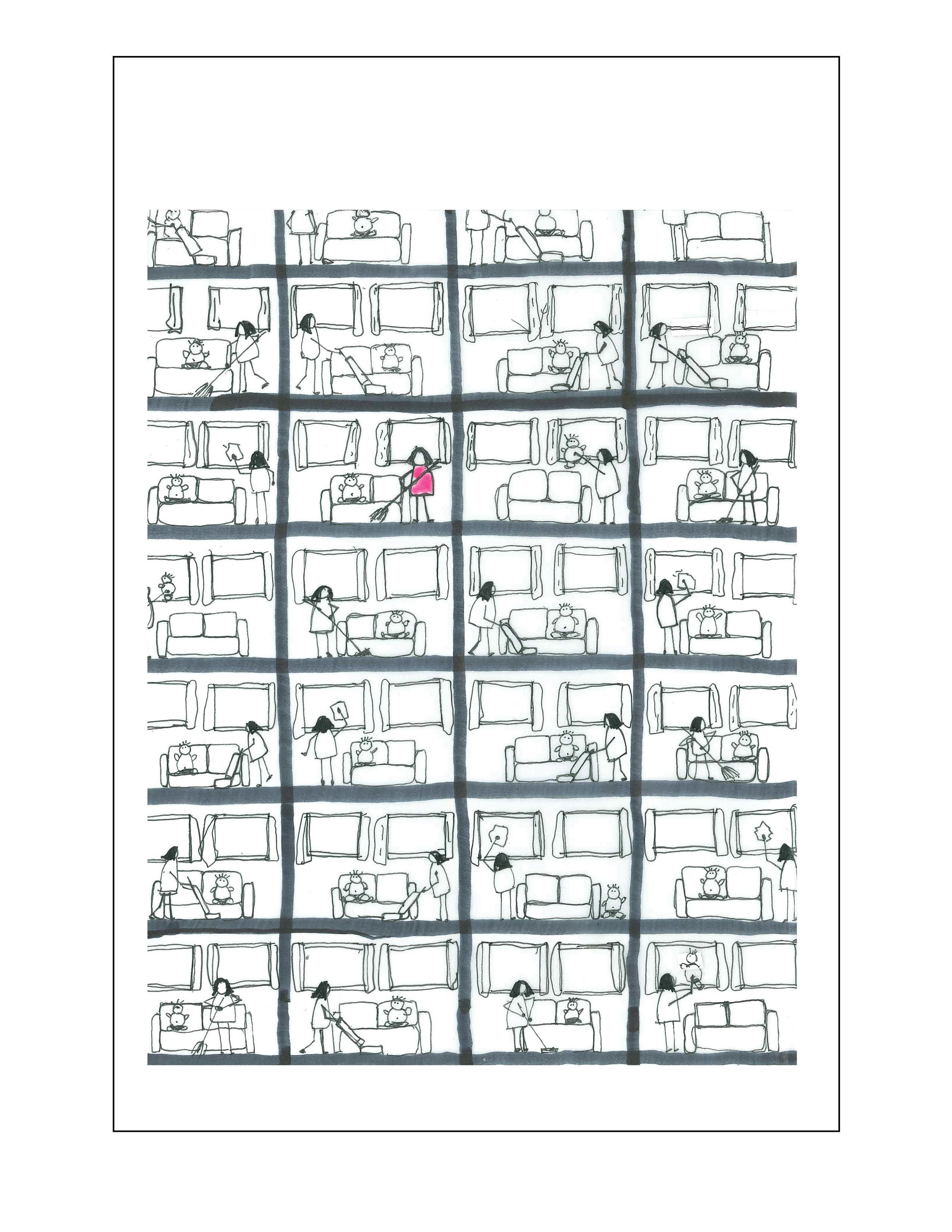

The image of Hong Kong can be distilled to the ubiquitous cruciform apartment towers and the iconic HSBC headquarters set against mountainous terrain. Both are symbols of efficiency, the former a typology developed to house millions of people on a small land mass, the latter (designed by Foster and Partners and completed in 1986) to optimize a work environment premised on flexibility and profit. While the Hong Konger labours visibly alongside her colleagues, the labour of each MDW is mostly confined to the apartment, where it is invisible to anyone but the immediate family. Her situation is replicated across Hong Kong, creating an atomized workforce that works an average of 71.4 hours per week, the result of the confluence of work and living spaces. While Hong Kongers in shared factories and offices retain the latent power of a collective workforce, the domestic worker’s one-to-one relationship with her employer denies her this mass agency: the architecture that frames her everyday experience weakens her political power, since it is infeasible for the Labour Department to enforce adherence to labour standards in hundreds of thousands of homes.

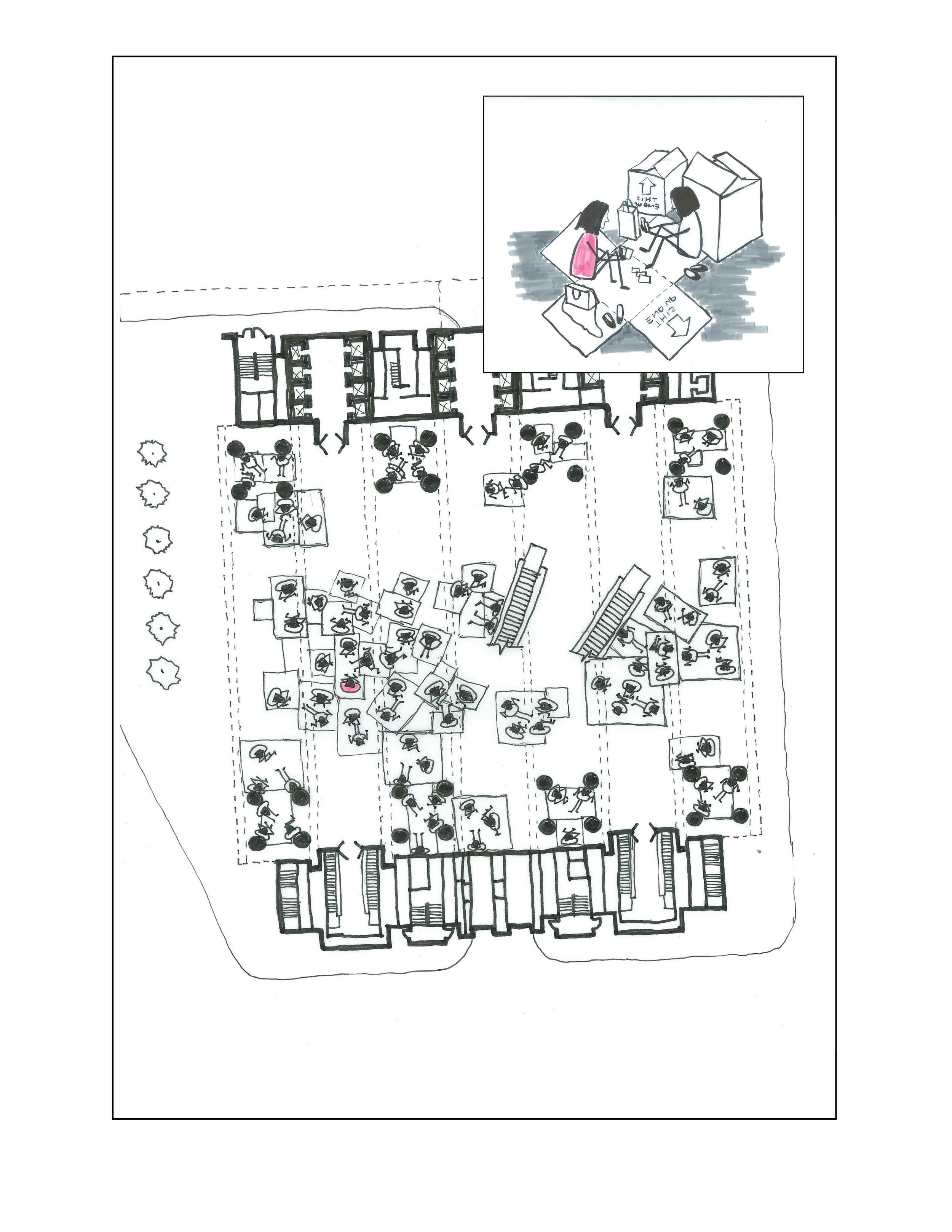

Each Sunday, the spaces these two women occupy flip. While the Hong Kong mother lounges at home, the domestic worker commutes to Central district, the commercial heart of the city. Every week, groups of MDWs meet at the same places and times to purchase cardboard from local hawkers to build ad hoc structures that become the venue for all matter of domestic activities from group-oriented dining and praying to individual napping and Skyping with family. Both women, either enclosed in concrete or cardboard walls, undertake self-care activities, re-claim nuanced identities beyond their jobs, and spend time maintaining familial relationships, whether defined by blood or along vectors of language and geography. For Hong Kong’s MDWs, gathering on sidewalks, pedestrian bridges, parks and lobbies is a pragmatic response to an urban landscape that was never planned with them in mind, in spite of which they’ve managed to tactically carve out space for their non-work-related lives—occupying architecture designed for business, in a district zoned for commerce, they often endure criticism from locals for “doing private things in public places.” But their presence both affords them the political agency of mass gathering and reveals the domestic workforce that keeps the households of Hong Kong running. The Sunday visibility of MDWs can be directly correlated to government policies that compartmentalize care tasks, keeping them within the nuclear family’s household instead of creating shared spaces in the city for these essential activities. The lack of space afforded to Hong Kong’s MDWs betrays a broader devaluing of the labour and people associated with the domestic sphere and outlines the physical and political space still to be claimed on the path toward gender equality.

Bio

Em Cheng is an architect and artist based in Toronto.

Jennifer Davis practices architecture, art, and independent curating on Toronto, Canada. She holds a Master of Architecture (2011) from the University of Toronto where she is a Sessional Lecturer. She has received awards and grants from the Canadian Centre for Architecture, Canada Council for the Arts, Graham Foundation, apexart, and the Ontario Association of Architects.