Power Lunch

By Stephanie Lee

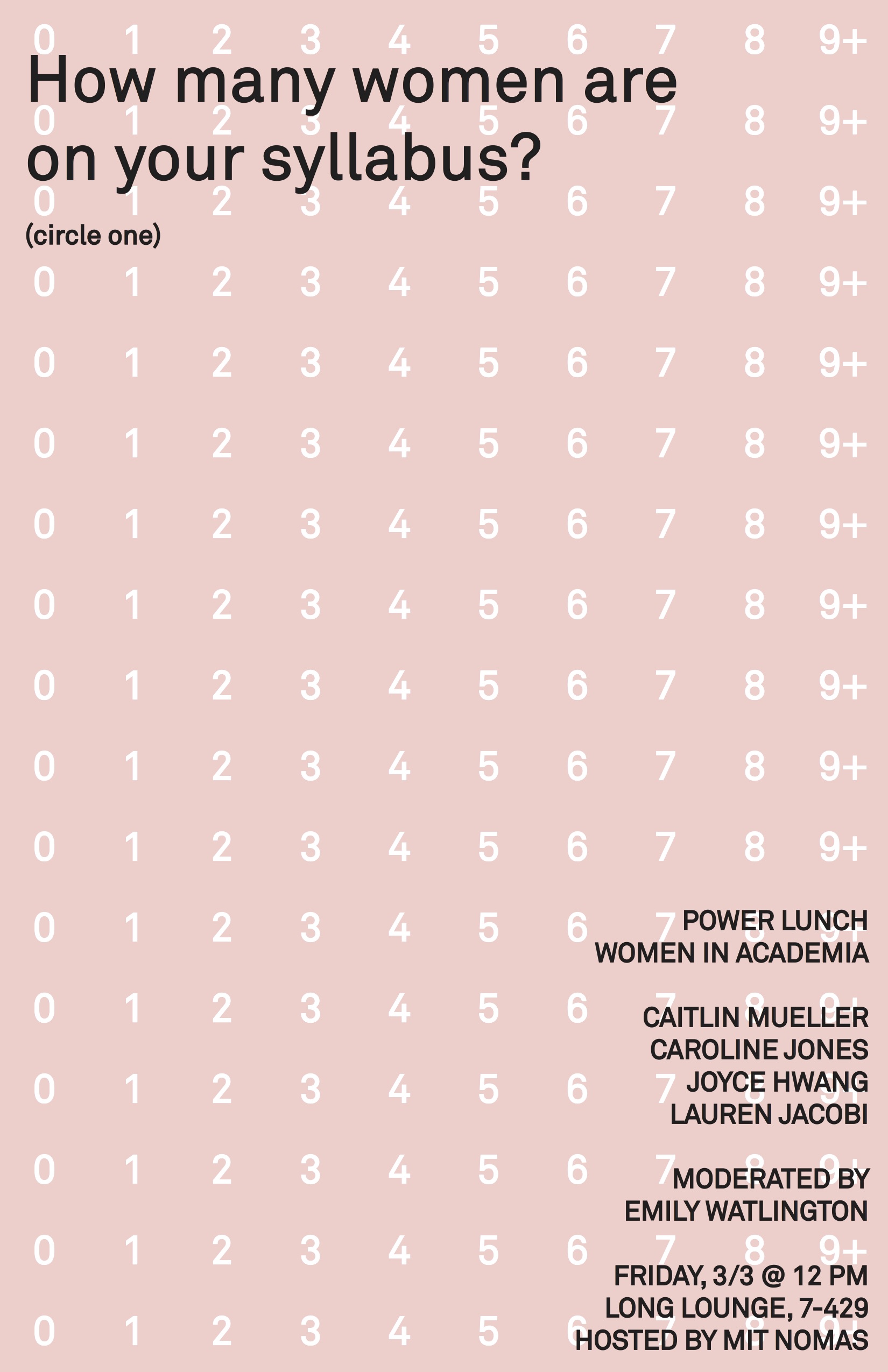

In the spring of 2017, I organized “Power Lunch,” a guerrilla conversation series at MIT, intended to bring together female architects and academics at various stages of their careers (junior faculty, tenured faculty, professionals). These talks, off-the-record dialogues led by female students, were envisioned to be a means of talking about how being a woman shaped their experiences in architecture. The first three Power Lunch conversations considered women's roles in architectural practice, academia, and the city. The fourth and final discussion, a round table between students and contemporary architectural activists, sought to distill the ways that those experiences and feminist narratives could be registered within our architecture.

I made the decision to organize the lecture series after reading about a canceled seminar at the School of Architecture at Yale University. Titled “Expanding the Canon,” the course was to cover the ways in which women and buildings designed by women were systematically written out of the architectural canon. When only one student registered, however, administrators made the decision to cancel the class due to low enrollment.

Reading about the cancelation of this seminar, which was intended to explore the neglected narrative of the achievements of female architects and to detail their systematic erasure from architecture history, was especially painful after the (then very recent) election of Donald Trump, who defeated Hillary Clinton despite his misogynistic rhetoric and behavior, including his apparent admission of sexual assault on the Access Hollywood tapes. The election and the course cancelation were unrelated events, but it was difficult to disentangle the impact of these two successive losses for women.

Organizing this women’s series was also a way for me to engage with the complex experience of being a female student at MIT. Women have historically been underrepresented at the school, a problem that MIT has tried to resolve through aggressive gender-based recruitment. While this increased effort has succeeded in generating greater enrollment by women, it has simultaneously given rise to the insidious myth that the women on campus are not inherently qualified to be at the school—that female students, benefiting from the institution’s need for representation by their gender, have an easier time gaining admission to MIT and get by on lower standards. The myth is pervasive in many corners of the student body, tacitly corroding the standing of female students and even female professors at the school. In a 2011 article, The New York Times acknowledged this dynamic, reporting: “Among other concerns, many female professors say that M.I.T.’s aggressive push to hire more women has created the sense that they are given an unfair advantage… But the primary issue in the report is the perception that correcting bias means lowering standards for women.”(1)

Women are thus viewed by some people on campus as beneficiaries of a kind of affirmative action, inherently under-qualified and perceived as having an easier way into the university as opposed to men, who "have no leg up." This view is not limited to silent corners of MIT’s current student body. Earlier this year, a Google software engineer named James Damore, who spent time at MIT as a researcher, circulated a memo claiming women were inherently less suited than men to roles in technology.

This belief is so pervasive that even presenting facts and hard statistics does little to undo the myth. In the 2016 Report on the Status of Undergraduate Women at MIT, it was observed that:

…[Undergraduate] women at MIT experience negative stereotyping and feel less confident than men, even though they perform as well or better than their male counterparts on standard metrics of academic success such as GPAs and graduation rates.(2)

Despite their ability to succeed at a level equal to or beyond the abilities of their male peers, many women at MIT continue to feel insecure about their capacity to perform. A common attitude prevails when it comes to discussing the dynamics of gender on campus: to admit that one is a woman at MIT and to frankly address the context of gender at the institution is to admit to being complicit in receiving some sort of assistance or having enjoyed some kind of imagined unfair advantage—and thus to admit that one is unqualified. Thus, many women on campus avoid addressing the subject of gender entirely, and it often seems that there is a fear of acknowledging or confronting that false narrative about women at MIT.

I don’t believe that most of the faculty, students, or administration at MIT’s School of Architecture actively subscribe to the notion of women on campus being inherently less qualified than men, but the sentiment is difficult to ignore or avoid completely while studying and working at MIT, a school that has been so vocal in its attempt to shed its image as a male-dominated school and yet remains predominantly male. Though the numbers of female students have increased in recent years, based on a report issued in 2017, both undergraduate and graduate women comprise less than one-third of the school. Just 22 percent of faculty members (of all ranks) are women.

Despite these numbers, the School of Architecture has felt relatively insulated from the conversation of gender inequity. Although women comprise only 29 percent of the faculty in the school, the women in our faculty are incredibly accomplished in their fields and are vocal, visible participants at the school. Moreover, MIT’s School of Architecture was one of the first schools to accept women. In 1890, Lois Lilley Howe became the first woman to graduate from MIT’s School of Architecture, going on to become the second woman in the United States to establish her own architecture firm.(3) In 1905, Marie Celeste Turner was admitted to the School of Architecture, becoming the first black women to attend MIT.

But despite—or perhaps because of—this legacy of diversity and openness in admissions for women, the subject of gender is almost never discussed in the School of Architecture. Female professors at the School of Architecture rarely talk about their experiences as women at the school or in the profession, instead focusing their conversations and presentations on their research interests and current projects. Once in a while, on the other hand, we will receive alerts that the women in our faculty have received awards elsewhere for their achievements and accomplishments as women in architecture—compounding the sense that our female professors may acknowledge their roles as women in the field broadly, but rarely on campus at MIT, as if a silent taboo against acknowledging gender persists in the department.

The lack of engagement with the female student experience at the School of Architecture felt like a contradiction when set against the relatively high number of prominent women in our faculty. The absence of open conversations about the experiences of women in architecture—in the wake of the canceled women’s seminar at Yale, Donald Trump’s election victory over Hillary Clinton, and the ongoing challenges faced by women at MIT—formed the basis of my motivation to organize this conversation series.

On the morning of our first lecture in February 2017, we re-positioned the chairs of MIT’s Long Lounge, where several school lecture series take place, into a medium-sized circle meant to garner a sense of intimacy and closeness and to reduce the hierarchical impression of traditional academic settings. I couldn’t stop thinking of the women’s seminar canceled for low enrollment as we set up the room. Our desire for intimacy mingled with our fears of low attendance, and so our first conversation featured a modest, close-knit arrangement. We set up two rows of chairs, creating seating for about twenty students, silently hoping that more would come. Would people think that this was a relevant conversation to have?

In the moments leading up to that first conversation, more and more students filtered into the room, adding chairs to that small circle. By the time the discussion began, Long Lounge had been filled to capacity. A respected female professor brought her young son with her to the event—visual evidence of the challenges many women face when entering the professional world and a signal to us that our new discussion series had the potential to fill a void for many women and young people in our community.

Women from various fields and experience levels came together during these events to discuss how being a woman shaped their experiences within their respective areas of work and study. These off-the-record conversations rangedacross topics, from the obstacles facing women in academia and professional life to the need for mentorship, from women’s achievement awards and raising children to the differences in tasks assigned to female and male interns.

We anchored our first session, which focused on women in the professional world of architecture, on four questions:

- As a practicing female, what are some of the interactions or biases in everyday practice that might go unnoticed?

- How does your practice specifically address or take action towards a feminist practice? How do you try to produce a more gender-equal/inclusive profession?

- What was visible in school/profession when you were first starting? How did you decide what kind of practice to have? (If practice itself can be designed?)

- What does a feminist practice look like?

The panelists were Sheila Kennedy, Professor of the Practice of Architecture at MIT and the principal of KVA; Andrea Leers, of Leers Weinzapfel, the first woman-owned firmed receiving the AIA's Architecture Firm Award; and Jennifer Bonner, an assistant professor at Harvard University Graduate School of Design and Director of MALL. Each of these women could have been featured as a lecturer to present their architecture and research without even mentioning gender. Instead, they joined us to share their experiences in the context of being women in the architecture profession.

While the questions were specifically oriented toward the practice of architecture and experience, our conversations tended to gravitate to the legitimacy and relevance of exhibitions, publications, and awards that focused entirely on the achievements of women. Particularly as we had a cross-section of women from a range of different moments in their careers and lives, the need for these gender-based achievement awards and exhibitions became a space of contention. Denise Scott Brown best encapsulated this feeling of conflict in "Room at the Top? Sexism and the Star System in Architecture,” when she wrote, “I am frequently invited to lecture at architecture schools, ‘to be a role model for our girls.’ I am happy to do this for their young women but I would rather be asked purely because my work is interesting.” This pervasive sentiment seems to be the one that underlies the desire to diminish the role that gender plays in structuring our experiences as students, as researchers, and as architects.

In the following lunches, we discussed what it meant to create a physical space for women, not only as a place for mentorship and bonding but also as a spacewhere women could feel physically secure. Within this conversation, we talked about the various ways in which women felt safe or felt unsafe within the city, focusing on the basic details (such as lighting and traffic) that make a street more hospitable to women.

While the subject matter of discussing women’s experiences in architecture was not revolutionary on its own, for us at the school it felt truly groundbreaking and legitimizing to be able to openly acknowledge that women do indeed have a unique experience in architecture, a unique set of challenges, and that it was valid to discuss the inequities within the profession. A few days prior to our first event, The Architect’s Journal and The Architectural Review published a series of surveys illustrating the insecurity that women face in the profession. Of the surveyed women, only 18 percent were certain that women had been fully accepted into the building profession, and 72 percent admitted to having experienced sexual discrimination, harassment, or victimization during their architecture careers. Among surveyed mothers, 59 percent believed that having children had a "detrimental effect" on their careers.

Mimi Zeiger, in an essay titled “On Gender” published in The Architectural Review, asked: “In honoring the ladies of design, do we risk divorcing them from the overall discipline, thus marginalizing their accomplishments, or do ‘women spaces’—hard-won outgrowths of equal-rights fights of previous decades— offer much-needed forums for discussion and action on the inequalities still faced within the academy and workplace?” The question was one that we grappled with during the conversation, but after the series of events in the past year, I feel strongly that these women-spaces, or places for women to come together both in solidarity (whether it be through movement building, achievement awards, exhibition, etc.) and in physical spaces, are necessary and valuable, particularly as our role in the profession still feels tenuous. With nearly every single lunch mentioning the need for both maternity and paternity leave, as well as the desire for mentorship, guidance, and solidarity with other women, it became evident that women face similar logistical obstacles.

As long as we are asking how it is that we balance work and life, how it is that we assert ourselves in the face of sexual discrimination, as long as we are getting paid less for our work, and as long as we are relegated to more menial secretarial tasks, these women spaces are necessary. The existence of those very questions, and the fact that our male counterparts are not asking them, confirms that inequality persists and is not just a figment of our imagination.

Simply, Power Lunch created the time and the space amid the regular lecture series cycle to explore what it means to be a woman in architecture today and how to engage with the conversation on gender without feeling like one was engaging in a lower form of conversation. Power Lunch highlighted narratives and experiences that are too often either dismissed or pushed aside. The goal of the lecture series was to address head-on the myth that women's rights—and, by extension, other social movements—and architectural design are incompatible.

Endnotes

1. Kate Zernike, "Gains, and Drawbacks, for Female Professors," New York Times, March 21, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/21/us/21mit.html.

2. MIT News Office, “Undergraduate students release Report on the Status of Undergraduate Women at MIT,” MIT News, February 25, 2016, http://news.mit.edu/2016/report-on-status-of-undergraduate-women-at-mit-0225.

3. “Notable Women Alumni,” MITWiki, last modified March 2, 2017, http://wiki.mitadmissions.org/Notable_Women_Alumni.

Bio

Stephanie Lee is a graduate student at MIT's School of Architecture and Planning. She previously organized Power Lunch, a discussion series at MIT for women in architecture, and is now trying to turn vacant storefronts into spaces for art and community.