The Breathing Grid

By Tammy Gaber and Thomas Strickland

The place of the body within architecture is framed and circumscribed through embedded and systematic ordinances with respect to both proportion and gender. The fact of the varied and complex gender identities and biological bodies that inhabit and, through use, shape the built environment to particular needs has traditionally been superseded and neatly ignored in favour of “ideal” male proportions. These imaginary figures assume a universal order. Both systems of architectural ordinance, that based on the male body and that based on abstracted units, negate bodies other than the ideal male. When deployed as the standard, these ordinances fan out into radiating grids of spatial determination. By assuming these conventions with respect to the measurement of spaces, architects embed predetermined modalities of personal place within spaces.

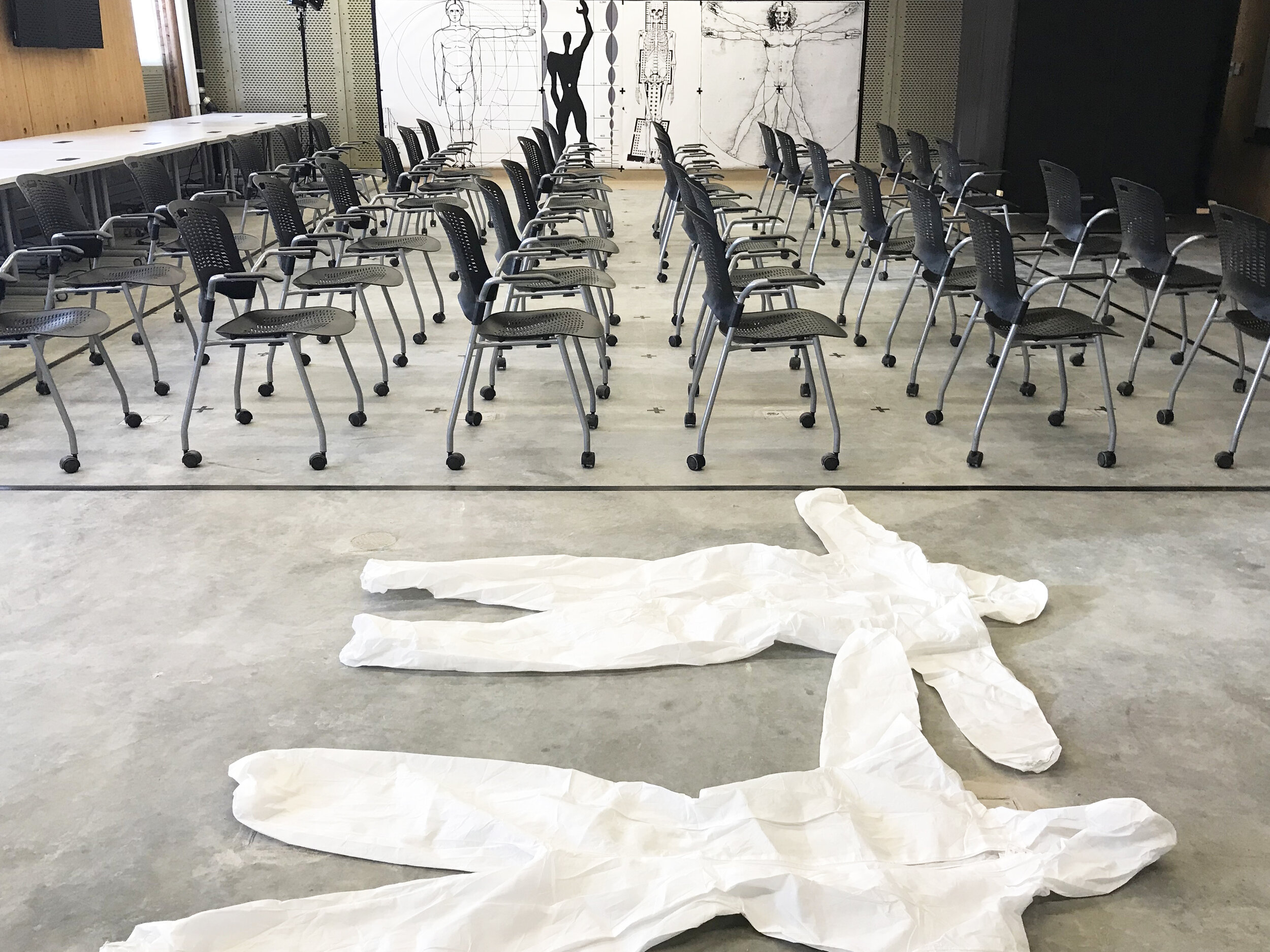

The Breathing Grid was an immersive installation created during an event at Laurentian University’s School of Architecture. The installation appropriated classroom facilities and 1:1 scale reproductions of historical and contemporary diagrams of body proportions commonly deployed in the production of architecture.

Included in these reproductions were Schwaller De Lubicz’s from The Temple in Man (drawn from the proportions of the ancient Egyptian architecture of Luxor),1 Leonardo Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man (based on the theories of the Roman architect Vitruvius), (2) Le Corbusier’s Modulor Man (the six-foot-tall hero of a detective novel), (3) and the Graphic Standard’s proportion standards for human scale in architecture (maximum and minimum values determined by the “normative” ideal of a six-foot-tall, able-bodied man). (4) These ancient, modern, and contemporary proportional theories, exclusively based on the ideal male body, inscribe proportions for teaching and designing architecture.

These reproductions were then measured, questioned, and deconstructed during a one-time, ten-minute performance. Dressed in identical white disposable coveralls, we interacted with each other and the scaled diagrams utilizing normative, binary-associated paint colours (red and blue) to first hand paint each other’s faces and later cover each other’s outfits in paint—Tammy turning Thomas blue and Thomas turning Tammy red. Framed within a black box, hidden from the audience’s view but for a live image filming from above and projected onto screens outside, this component of the performance masked our genders, and instead expressed an intimate and shared struggle to be acknowledged by the frame of architectural ordinance.

Our movements were paced and choreographed to ambient background music. On cue, we departed the box revealing ourselves to the audience, who up to this point were unaware it was a live performance. Once out, we moved in lockstep to the scaled reproductions, using our differently sized and biological bodies, male and female, to produce traces in paint of our interactions with, and defiance of, the rigorous spatial norms established by the reproductions of idealized proportional bodies.

As professors in the school of architecture, we were aware of the heightened impact appropriating a classroom, which is designed to reify teacher-student relations, would have on an audience familiar with such spaces. The room was emptied of all signs of day-to-day use and was reorganized and detailed to make visible the raw parameters that underpin traditional teaching environments. (5) An ordinance at the centre of the performance space/classroom fixed a limited number of chairs within a grid marked onto the floor. Recorded through various devices aimed in multiple directions, the spectators became a part of the performance when they adhered to, or broke from, the grid in order to negotiate their choices of movement and reactions to the experience. The audience/participants observed the projections of our bodies painting each other on the classroom screens at the front of the room. Upon emerging from the black box, we shifted the viewer’s gaze 90 degrees to the reproductions, at which point the audience/participants had to choose whether to remain within the order of the grid or shift their bodies in various degrees to view our interaction with the scaled images.

After an additional ten minutes we exited the room, leaving the music to fade away, and the audience/participants unattended to in silence. Eventually the doors to the room were opened allowing others waiting outside to enter. For the next hour, the audience/participants shared verbal recreations of the event with those unable to attend. While the performance space/classroom only accommodated 36 audience members, approximately 90 people had formed a line outside. When allowed in, those waiting outside became the audience for the stories told by the audience/participants, making them performers themselves.

According to architecture student Sonia Ekiyor-Katimi:

To me, this process was especially important. My own thesis dealt with the dangers of a single human model on our greater urban communities and how the traditional grids in architecture may allow violence to people whose bodies are never considered during architectural design. This performance absolutely validated exercises undertaken while writing and completing my thesis.

This performance piece had a huge significance to me, within the architecture school, and for members of the community for a few different reasons. In this day and age of architecture, we have begun to realize more about how suddenly bodies move through space and stepping away from the Vitruvian model and scale so conventionally used in architecture.

To see this freedom from Vitruvius personified and performed by members of faculty is an ultimate exemplar of the phrase “lead by example” especially so because it was performed in a space known to students already. Students who watched gained confidence for more diverse human consideration while designing architecture and members of the community were made to think of their own bodies' relationship with their everyday architecture. The use of paint on the bodies of the performers was crucial to marking the grids. This created a continuous installation from a performance.

The marks of these new bodies on historically referenced scales and grids gives the clear imagery for all to see the deviance from the tightly wound traditional grid of what the “perfect body” would be as a unit of measurement in architecture. (6)

Endnotes

(1) R.A. Schwaller de Lubicz, The Temple in Man, Sacred Architecture and the Perfect Man, trans. Robert & Deborah Lawlor (Rochester: Inner Traditions International, 1977).

(2) Carolo Pedretti, Leonardo Da Vinici: Art and Science (Surrey: TAJ Books, 2004). And Vitruvius, The Ten Books of Architecture (New York: Dover Books, 1960).

(3) Le Corbusier, The Modulor: A Harmonious Measure to the Human Scale, Universally Applicable to Architecture and Mechanics (Basel & Boston: Birkhäuser, 2004). First published in two volumes in 1954 and 1958.

(4) American Institute of Architects, Architectural Graphic Standards, 12th Edition (Hoboken: Wiley, 2016).

(5) Elizabeth Ellsworth, Places of Learning: Media, Architecture, Pedagogy (Routledge, 2005), 4–5.

(6) Sonia Ekiyor-Katimi, email exchange with Tammy Gaber, March 2020.

Bio

Tammy Gaber is an associate professor at the McEwen School of Architecture, Laurentian University. She completed a SSHRC-funded research project which led to her forthcoming book with McGillQueen’s University Press, Beyond the Divide: A Century of Canadian Mosque Design and Gender Allocation and has published on gender and architecture with a chapter in the forthcoming Global Encyclopedia of Women in Architecture, published by Bloomsbury.

Thomas Strickland is an assistant professor in the McEwen School of Architecture, Laurentian University. He has written for numerous art and architectural journals and recently published a chapter in Healing Spaces, Modern Architecture, and the Body. He also works as an artist. Recent exhibits include Breathing Grid and Formerly Known as the Glass Ceiling.