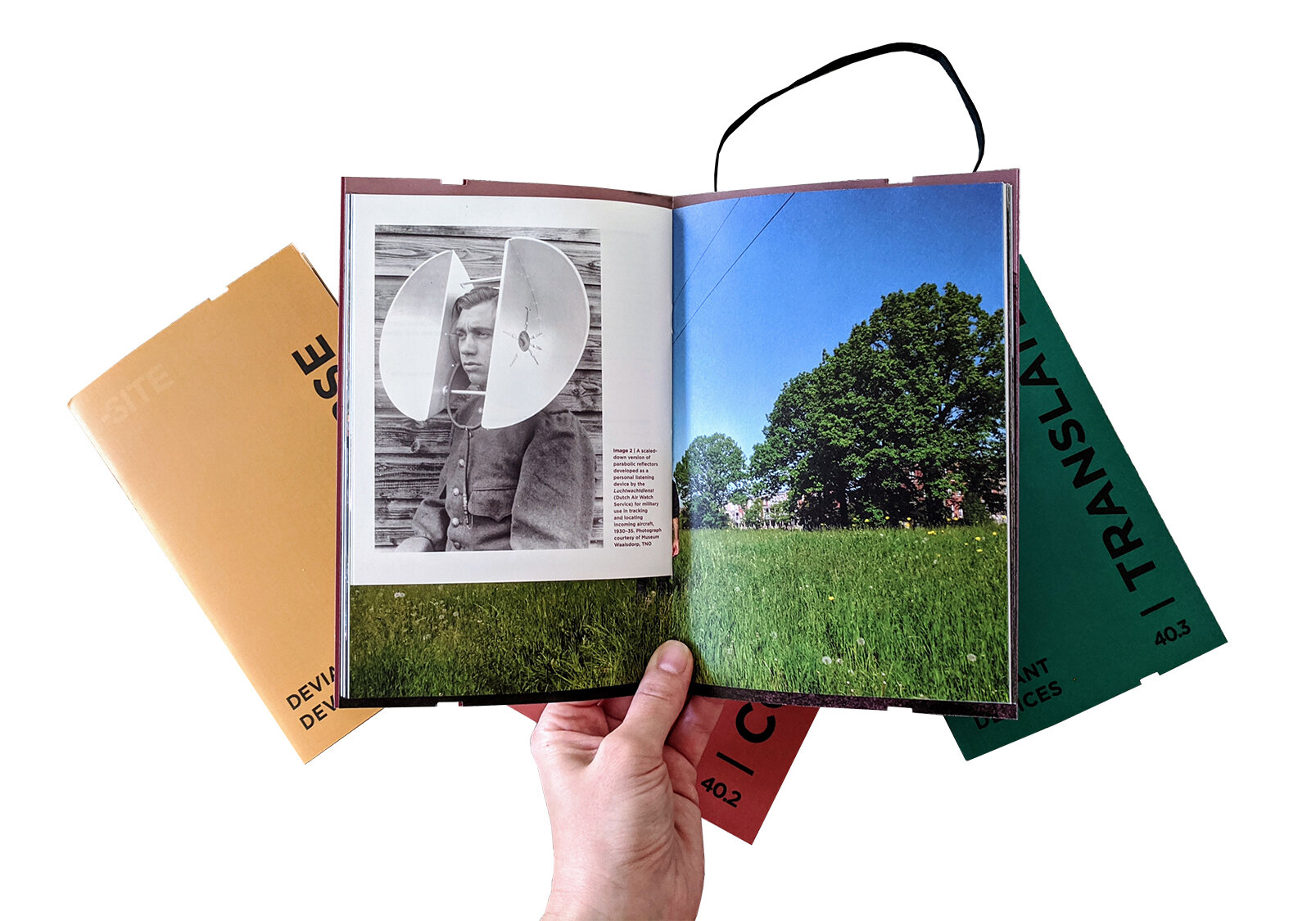

Volume 40.3 Translate

Text by Ruth Jones and Aisling O’Carroll

There are over 100 languages in Google translate. You can translate text and speech, pull out words from an image, find your way through idioms you’ve never learned and probably never will. Tools like this are closed systems, black boxes that excel at communicating information. They are modern-day enigma machines: meaning vanishes into them and reappears on the other side, passing through nothingness to become action. “Is a translation meant for readers who don’t understand the original?” the German theorist Walter Benjamin asks in his 1921 essay “The Task of the Translator.” Translation machines like Google’s seem to answer, “Yes.”

But is communication translation’s only end? Consider a survey marker that translates between an abstract set of measurements and the physical landscape. It communicates something, sure, but it also makes it present, and in doing so it acts on and is acted on by its environment. On the map, the coordinates convey information about the distance between points, the height of an elevation. On the mountain this information competes with other, more immediate forces that shape the landscape, from tectonic movements to landslides, floods, and weather. Over time, the translation becomes unstable.

Benjamin’s answer to his question was “No.” He thought of translation, like any type of writing, as a form, one particularly in tune with the distance between two things that mean the same thing in different ways. How does this work outside of language? A lens finds a rainbow in white light, parametrics channel solar time into an (apparently) digital output, an underpass opens to the city around it, and virtual worlds put the rules that constrain us into a player’s hands, each one uncovering hidden potential in the harmony between disparate ways of being.

Image 1 | The Enigma machine. Photograph courtesy of Museo Nazionale della Scienza e della Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci, Milan, Italy (caption by Aisling O’Carroll)

The Enigma machine is an encryption device invented by the German engineer Arthur Scherbius following the end of WWI. It was first used in commercial markets but later adopted for military applications—most (in)famously used by the Germans in WWII to transmit coded messages. The Enigma’s encryption relied on an electromechanical rotor mechanism that scrambled the twentysix letters of the alphabet, encoding each letter typed into its keyboard with an alternate letter. The encryption settings were changed each day or per message. The complexity of the machine’s encryption made the task of decoding messages incredibly difficult—many believed impossible. It wasn’t until 1940, when British cryptologists installed the first functioning decryption machine, the Bombe, that the Allied powers were able to begin decoding German communication.

Image 2 | Monument marking a survey point at Palliser Pass, British Columbia, 1916. Photograph courtesy of Government of Canada, Library and Archives Collection

(caption by Aisling O’Carroll)

Monument markers are physical objects used to mark key survey points on the Earth’s surface. They translate particular coordinates and triangulation points from the measured, calculated, abstract space of a cartographic survey to the landscape as a physical manifestation of our human will to measure, define, and bound space. While monument markers today are typically simple castmetal disks set flush on rock edges or paved surfaces, earlier, monumental markers made marked points visible from a distance, giving their physical manifestation a significant presence while enabling a visual connection between survey points.

In this pamphlet:

Devices for Summoning Rainbows by Caitlind r.c. Brown

Gnomo by Jon Enns

Video Urbanism by Luke Pearson and Sandra Youkhana

Translating the City interview with Ilana Altman