A Patronage Model for New Public Art

// Collecting Rafaël Rozendaal’s Art Websites

By Marie van Zeyl

Information technologies have transformed the creative industries, fostering new methods of art production. For Dutch-Brazilian internet artist Rafaël Rozendaal, his laptop is the primary place of creative production. Unconstrained by a bricks-and-mortar studio, the web browser is Rozendaal’s proverbial canvas. (1) Unlike a painting, his websites benefit from a widespread and placeless existence. Compatible with different screen sizes, they are formatted to expand like air that fills a space. Through the internet’s network systems, users may discover his art websites accidently through web-surfing activity. In the early 2000s, people began to find Rozendaal’s work through www.stumbleupon.com, an iconic discovery search engine that suggests web content to its users. This is exactly the type of viewership Rozendaal is striving for, integrated into the network. Rozendaal’s main priority is to keep his websites in distribution, so that his works may function in a democratic online space that is more relaxed and collaborative than a museum or gallery.

The advent of web browsers in the mid-1990s provided artists with a new medium. Web browser art was first created by a small European collective that burgeoned out of an online mailing list called Nettime. Conviviality characterized this group, which included Russian artists Olia Lialina and Alexei Shulgin, British artist Heath Bunting, Slovenian artist Vuk Ćosić, and the Barcelona-based collective Jodi (Joan Heemskerk and Dirk Paesmans). The group would later be deemed pioneers of “net.art,” which opened the door to new a definition of what art could be. For them, web browsers were alternative spaces to produce and exhibit art outside the traditional workings of the art establishment in a proverbial “museum without walls,” a term first coined by French art historian André Malraux. (2) No longer constricted by the drawbacks of a brick and mortar building, net.art could be viewed in a casual online space unlimited by geographical scope or time. The internet expanded what an exhibition venue could be, and allowed net.artists to become curators of their own works. (3) Net.art was a strategy to de-commodify art through the democratic ethos of cyberspace, plugging into a new public domain. Maneuvering away from the buy-sell model of tangible objects in an exclusive art market, art websites embrace the internet’s self-governing and collaborative structure. (4) The group was championed in the academic sphere for existing in an environment that was unimpeded by the agendas of art dealers, state institutions, or corporations. (5)

The idea that net.art would remain outside the workings of the art market was a utopian notion: the art market absorbed the new medium in the early 2010s. Phillips auction house partnered with Tumblr and Paddle8 to present Paddles ON!, a digital art auction, in New York. The first of its kind, it included digital works by a second-generation of internet artists, those labeled under an umbrella of “Post-Internet.”

Post-Internet artists are criticized for producing works that possess an element of tangibility, so that they may be oriented towards the buy-sell model of the art market. But the label misconstrues the motivations of different artists under a large umbrella that encompasses a diverse set of artistic practices.

Rozendaal’s art websites reflect a reverence for the art historical grid as a symbol of modernity. Each website is composed of miniscule squares called pixels that create the image. In homage to Piet Mondrian, Dutch master of Neoplasticism, Rozendaal brought Broadway Boogie Woogie (1942–43) to life with a Flash animation of moving Mondrian cubes. Influenced by conceptual artist Sol LeWitt, Rozendaal divides the digital space into a grid and sets rules for how the viewer may click around the page to interact with the work. Electric boogie woogie .com (2010) is a positive statement about the impact that technological innovation will have on the future of contemporary art.

While aesthetically and conceptually driven, economic value is at the core of Rozendaal’s art websites. RR Haiku 202 reads: “the sooner you pay me. the sooner, i’m happy.” (6) In addition to producing art websites, he also produces art objects such as lenticular works, tapestries, and installations. These works differ from his art websites, as rare art objects that can be easily traded in the market. Conceptually, however, these tangible works remain an extension of the online sphere. Rozendaal’s lenticular paintings capture a moving image in an analogue object, mimicking the digital process of an animated GIF. With four frames superimposed, they possess the illusion of depth and movement. Due to the ubiquitous nature of network systems in daily life, it is natural that Rozendaal would seamlessly go back and forth between online and offline formats. (7) He rejects the label “Post-Internet,” which suggests the internet’s insignificance or the idea of “after the internet.” Unwilling to be placed into a defined box, Rozendaal is exemplary in how he blurs the dichotomy between online and offline formats. He creates both tangible and intangible works that can exist freely online and still be traded in the art market.

Despite the geometric rigor Rozendaal draws on, his work participates in a de-spatialization of art practices. Internet artists have constant access to their studio, which travels with them on their devices. (8) With a laptop and access to the network, artists may assume the role of curator of their own works. Art that resides online gains a wide audience due to its greater accessibility in comparison to the confines of location and time in a traditional exhibition space. This paradigm empowers the artist to circumvent institutional models of collecting, exhibition, and viewership.

COMBINING ACCESSIBILITY WITH EXCLUSIVITY

Collecting art is typically associated with tangible objects. Concepts such as fame, rarity and uniqueness boost the economic, cultural, and symbolic value of art. (9) This model upholds the idea that art is a luxury, reserved only for those who can afford to buy in. Lacking the materiality of a painting, a collector of an art website is unable to hold the work in their hands or hang it on a wall. Instead, art websites are only made material through the technological devices that we carry. Christiane Paul described this phenomenon as Neomateriality, where the physical space has been rendered obsolete. (10)

It’s difficult to reconcile the accessibility of the internet with the art market’s greed for exclusivity. The traditional notion of complete ownership is largely compromised when an artwork is online. Rozendaal has found a solution to this paradoxical situation through the development of his “Website Sales Contract” which also acts as a tangible “Certificate of Authenticity” for collectors who acquire his works. (11) In the environment of the internet, a domain name is the only rare entity and unable to be copied. When a work is acquired, the title found in the location bar of the URL is updated to include the name of the collector (“collection of…”) as a guarantee of ownership over the unique work. In return, the collector must keep the website online and accessible to the public in perpetuity. (12)

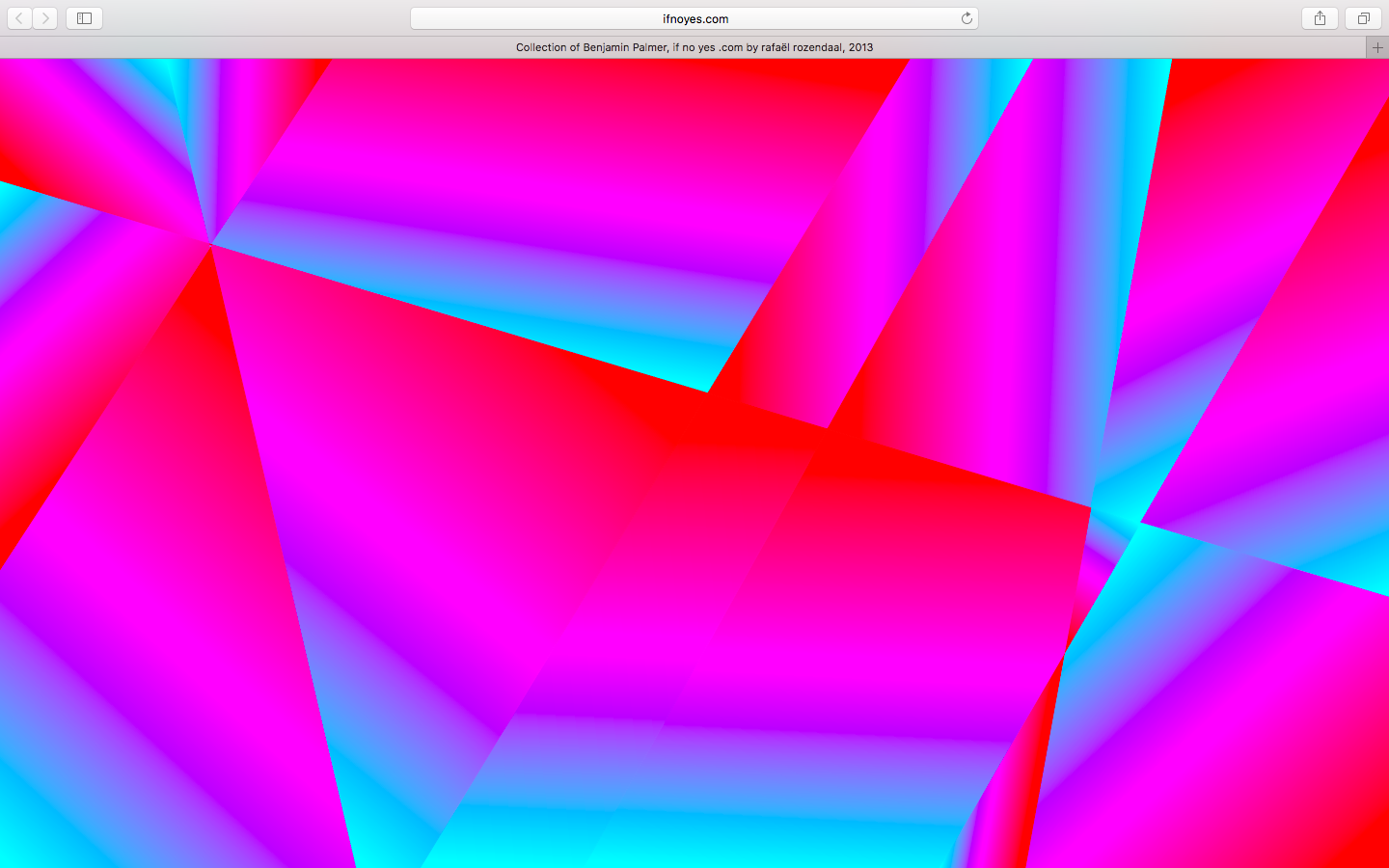

Paddles ON! demonstrated the viability of internet art on the market with sales that reached market records. A new demographic attended the auction, allured by the marriage of art and tech. With over 500 people present, 80% of the twenty lots were sold. (13) One work included was Rozendaal’s art website if no yes .com (2013), which was acquired by Benjamin Palmer for $3,500. Following the auction, Rozendaal transferred the ownership of the URL to Palmer, as an exclusive collectible. Maintaining the democratic ethos of the internet, the work continues to be accessible to all who type the domain name (www.ifnoyes.com) into their web browser. Rozendaal’s art websites challenge the traditional notion of complete ownership and prompt a perplexing question: Why would collectors be motivated to own an art website that is already available to them on the internet?

A NEW TYPE OF PUBLIC ART

Collecting an art website is more than just a transaction. Collectors become custodians, responsible for the work’s relationship to a distributed audience connected through the network architecture of the internet and via a remote, third-party server. With sharing culture as the zeitgeist of contemporary society, art websites are discovered online in a similar way someone would stumble upon a public artwork in a park. As placeless entities, they become public experiences, shared through everyday channels such as social media or online community spaces.

Collectors Almar and Margot van der Krogt own Rafaël Rozendaal’s work much better than this .com (2006), which has garnered worldwide attention for its appealing iconography. Colourful and Pop-inspired, the Flash animation shows a silhouetted couple kissing, with each kiss changing in colour. much better than this .com has developed a life of its own on private network systems as a popular viral experience. The meaning of the work is informed by the context of the sharing culture within the digital space, accessing a wider demographic than possible in a museum or public gallery. This adds an emotional appeal to collectors, as safeguards over famous artworks. much better than this .com has a global audience in the tens of millions, and has been viewed in both private and public contexts. This includes Midnight Moment, a digital art exhibition in Times Square, that showed the work from 11:57pm to midnight during the month of February for Valentine’s Day. (14)

Accessible to anyone, anywhere, anytime, art websites transgress the traditional viewership model of a mainstream art institution as well as the exclusivity of a private collection, and allow artists to make direct contact with their audiences. (15) In conservative institutional spheres, art is exhibited in an enclosed space with white walls existing “untouched by time and its vicissitudes” displaced from its socio-political context as “assurance of a good investment,” its architecture often modeled after Brian O’Doherty’s white cube. (16) In the online space, art websites may function independently from institutional agendas of exclusivity, and possess a democratic ethos by remaining connected to the context of the internet. (17)

Forward-thinking museums that collect art websites must project the work onto a screen for exhibition. By removing the work from the material specificity of the internet, the website becomes an enigmatic object enshrined by the institutional sphere. (18) At the same time, advertising screens like those used in Midnight Moment are effective platforms for public, digital art. On May 24, 2012, Rozendaal was invited by the New Museum to exhibit a selection of his websites in a one-night exhibition in Seoul Square on the world’s largest LED screen. The exhibition was inspired by the prophecy of Nam June Paik, a pioneering video and digital artist, who predicted that “one day all skyscrapers would be covered with screens and moving images.” (19) Facilitated by the museum and connected to the history of digital art through Paik’s words, the exhibition both institutionalized Rozendaal’s online work and highlighted its placeless existence in a public sphere, by connecting the city square to the open network.

When a museum’s collection can exist simultaneously as part of the urban fabric and as lines of code, accessible at all times and in all places, the dichotomy between the physical and the digital is blurred. The individual and institutional collectors who acquire art websites are interested in the sociological value of the creative medium, intrinsically connected to the contemporary technological environment. At the 2014 DLD Conference in New York, Rozendaal said: “Buying one of my artworks is an act of vanity and generosity.” (20) The collector becomes the safeguard over the longevity of the art website, who must maintain and preserve the work in perpetuity. As financiers for Rozendaal’s legacy, his collectors, both private and institutional, are transformed into stewards.

TOWARDS EPHEMERALITY

Collecting dematerialized art is not a new pursuit; Conceptual art from the late 1960s and early 1970s assaulted the modernist art object and rejected upper-class conservative ideologies responsible for the evils of capitalism that promoted the Vietnam War through strategies of dematerialization. (21) Rejecting of the idea that art is a luxury, Conceptual artists produced artworks that might be freed “from the tyranny of market orientation.” (22) Lucy Lippard documented the evolution of the dematerialization of the Conceptualist art object in the historical timeframe from 1966 to 1972 in the book Six Years (1973). When she began the project in 1969, Lippard did not believe that the art establishment could absorb the works made by the Conceptualists. Since the art market upheld the idea that materiality of art was paramount, Lippard did not consider that there would be demand for dematerialized art. (23) Yet, upon the conclusion of her book, Lippard reflected that her hope that Conceptual art would remain outside the workings of the art market was a utopian notion; any form of art can be commodified and sold on the market. With collectors “greedy for novelty”, all escapes from the institutionalized art world are temporary, only to be “recaptured and sent back to its white cell.” (24)

Internet art’s presence in the art market brings new discussions about the importance of the physical object for collectors as well as the spaces we consider public for purposes of display. Conservation of an art website is crucial, due to the medium’s ephemeral and vulnerable quality in an ever-changing technological environment. A work’s preservation can be a difficult and expensive endeavour, requiring a prolonged relationship with the artist and continual financial investment in the work. With constant access to the network, through our phones, laptops and other devices, the creative landscape has forever been altered. Rafaël Rozendaal has exhibited his art websites on the largest screens in the world on multiple viewing screens, in both private and public settings. He has also expanded on this exhibition model with his successful BYOB (Bring Your Own Beamer) project: a series of one-night exhibitions, where local artists bring their projectors and exhibit their art websites in community spaces across the world. (25) The event encourages curators and artists to exhibit their online-based works on the screen, in a symbolic rejection of the binary online/offline. While we still live in a society that upholds tangibility as an important aspect of an artwork, work like Rozendaal’s encourages us to embrace the accessibility and ephemerality of art created for a new model of public and private life.

Endnotes

(1) Rafaël Rozendaal, “Everything Always Everywhere,” DLD Conference NYC, filmed 2014, posted May 7, 2014, accessed August 7, 2018, http://dld-conference.com/videos/QwRL8cxkkCA.

(2) Julian Stallabrass, “The Aesthetics of Net Art,” Qui Parle 14, no. 1 (2003): 50.

(3) Rachel Greene, Internet Art (New York and London: Thames & Hudson, 2004), 21.

(4) Rachel Greene, “Web Work: A History of Internet Art,” Artforum, May 2000.

(5) Julian Stallabrass, Internet Art: The Online Clash of Culture and Commerce (London: Tate, 2003).

(6) Rafaël Rozendaal, RR Haiku 202, webpage, https://www.newrafael.com/rr-haiku-202/.

(7) Ian Wallace, “What is Post-Internet Art? Understanding the Revolutionary New Art Movement,” Artspace, May 18, 2014, accessed August 7, 2018, http://www.artspace.com/magazine/interviews_features/trend_report/post_internet_art-52138.

(8) Lauren Cornell and Ed Halter, Mass Effect: Art and the Internet in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2015), xviii.

(9) David Lowenthal, “Counterfeit art: Authentic fakes?,” International Journal of Cultural Property 1, no. 1 (1992): 93.

(10) Christiane Paul, “From Immateriality to Neomateriality: Art and the Conditions of Digital Materiality,” International Symposium on Electric Art (ISEA) (New York: The New School, 2015), 2.

(11) Rafaël Rozendaal, “Art Website Sales Contract- 2014,” webpage, http://www.artwebsitesalescontract.com.

(12) Ibid.

(13) “Phillips and Tublr Announce the Results of Paddles ON!,” Phillips, October 15, 2013, accessed August 7, 2018, https://www.phillips.com/press/2013/NY-Paddles-On-Results-Oct-2013.

(14) “Much Better Than This: February 1, 2015–February 28, 2015, Rafaël Rozendaal, Times Square Advertising Coalition,” Times Square Arts, accessed August 7, 2018, http://arts.timessquarenyc.org/times-square-arts/projects/midnight-moment/much-better-than-this/index.aspx.

(15) Stallabrass, Internet Art, 129.

(16) Brian O’Doherty, Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 7.

(17) Christiane Paul, “Flexible Contents, Democratic Filtering, and Computer-Aided Curating: Models for Online Curatorial Practice,” in Curating, Immateriality, Systems: On Curating Digital Media, ed. Joasia Krysa (New York: Autonomedia Press, 2006), 81.

(18) Christiane Paul, Digital Art (Third Edition) (London: Thames & Hudson, 2015), 23.

(19) “24 Hours in Seoul,” New Museum, July 18, 2012, accessed August 7, 2018, http://www.newmuseum.org/blog/view/24-hours-in-seoul-1.

(20) Rozendaal, “Everything Always Everywhere.”

(21) Lucy Lippard, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966–1972 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972), xiv.

(22) Ibid., xxi.

(23) Ibid.

(24) Ibid.

(25) Rafaël Rozendaal, BYOB (Bring Your Own Beamer), webpage, http://www.byobworldwide.com.

Bio

Marie van Zeyl holds a BA from Trinity College, University of Toronto, and an MBA in Arts and Cultural Management from the Institut d’Études Supérieures des Arts in Paris, France. Fascinated by the intersection of technology and the visual arts, Marie wrote her Master’s thesis on collecting web browser art.