How (Not) to Preserve Yourself

By Lan Florence Yee

In the early 2010s, a trend of adding queer narratives onto vintage photographs made the rounds on tumblr.com. The implications of suggestive looks, hand-holding, and eccentric dress inspired an internet generation to form histories of kinship and resilience amid public silence. To the chagrin of thousands of queer youth, a quick reverse image search easily revealed their made-up origins. These cases danced around my mind when I was parsing through an archive of Chinese-Canadian women in Sudbury. I paused most often on images of school dances, family outings, and young friendships. What was I looking for?

We demand evidence of our communities, often for good reason: to imagine ourselves in a larger narrative; to understand our lineages and legacies; to affirm our belonging, conditional as it may be. And yet, even as queer and racialized people are gravitating towards archival practices—from which we were once excluded—the form of the archive itself still retains the structure of the problem: its inherently limiting boundaries of authority, (in)accessibility, ethnographic classification, and penchant towards legible representation. How do we hold space for the unrecorded, the unrecordable, and the yet-to-be-recorded? What if our desire for documentation might be damaging? The challenges of commemoration beckoned me to consider what queer theorist Jack Halberstam refers to as “new forms of memory that relate more to spectrality than to hard evidence, to lost genealogies than to inheritance, to erasure than to inscription.”

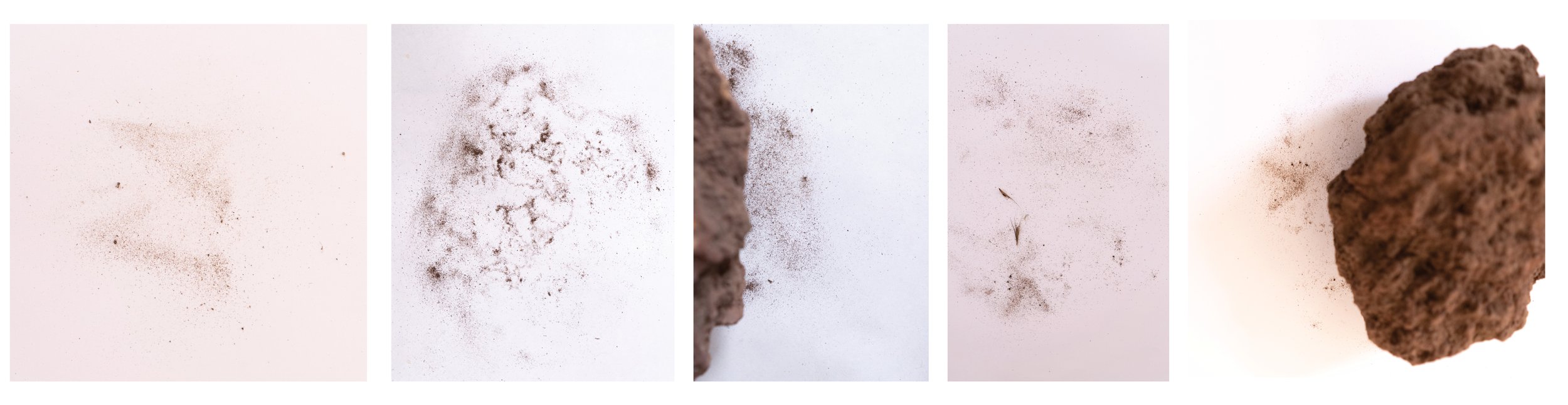

My ongoing series of embroidered watermarks is a first attempt at contending with the incomplete business of documentation by taking cues from traditional printing processes. The term “proof” is used to mean a preliminary stage of work, a state that requires flexibility, responsiveness, and consent. The series’ first image is a photo of the Anti-Displacement Garden, an outdoor patch of soil that I helped cultivate as part of Tea Base, a queer grassroots collective in Tkaronto’s Chinatown. In the midst of the space’s commodification by a cannabis company, the public seating on the brick path was taken away. That day, I coincidentally found a set of chairs on the curbside and decided to bring it down as a temporary measure. In the laborious process of interrupting the printed image with embroidered text, I wished to vicariously return the scene to a stage of unfinishedness, unable to be claimed or owned. This ephemeral step in the development process relies on a back-and-forth between the printer and the photograph’s keeper, an exchange that will be invisibilized in the final product for the sake of simplicity. Likewise, the garden is the sum of the efforts of dozens who committed to everyday acts of watering, weeding, harvesting, treating diseases, talking to neighbours, answering curious strangers, inviting people to join the hot pot, and being an accomplice to the struggle against displacement. These haphazard relationships are the foundation of a monument to collectivity, precarious as it may be.

On the other hand, invisibility can function as an escape from the confines of a limiting representation. The second of the series started with a photo of my feet next to my partner’s in her Scarborough home in 2019. It was around July, Pride month in this city. Rainbows, flags, and feather boas littered Church Street, but we also made time for quiet queerness, delighting in the mundane, tedious, and political nature of chosen family. Unlike then, the use (and tokenization) of queer visibility had almost completely disappeared in mainstream marketing during 2020, seeing as it was no longer profitable or “relevant” amid stay-at-home orders. Eschewing what Dai Kojima calls “institutionalized forms of queer visibility,” the PROOF series opts for an anti-spectacular reading. Across the unpoetic structure of a watermark, the image puts the attention on ambiguous and minor forms of intimacy, somewhere on the spectrum between refusal and the lauded feminist mantra of radical vulnerability. I call this willing, yet opaque, confessional work “thick legibility.” It complements the need for agency and distance when diving into the treacherous waters of auto-biographical art, particularly as racialized queerness has been increasingly marketed as a hypervisible commodity in the arts sector as well. The watermark is an appropriation of a commercial obstacle, becoming a boundary to its consumer-audience, attempting to mitigate the colonial impulses to explore, explain, and exploit. The word PROOF stands both as a porous barrier to the subject and a cheeky response to our inclination towards preserving evidence.

Just like their namesake, the PROOF series is nevertheless an incomplete job. Unable to capture all facets of lived experiences through photography and print, the textiles are an ode to self-defeat. Rather than seeing an archive for its fossils, a willingness to eschew permanence and stability sees the cracks. They are acknowledgements and pathways to ever more bountiful narratives that we will never know, but which will push us ever further than we could have imagined. As José Esteban Muñoz writes, queerness is a horizon, to which we have not yet arrived. Maybe those “fake” Tumblr posts had it right all along. Speculative evidence could well open more doors than a limited truth. After all, when my partner was reminded of them, she happily told me that their lack of authenticity did not seem to matter to her.

Bio

Lan Florence Yee is a visual artist and recovering workaholic based in Tkaronto/Toronto and Tiohtià:ke/Montreal. Their practice uses text-based art, sculpture, and textile installation through the intimacy of doubt. Along with Arezu Salamzadeh, they co-founded the Chinatown Biennial in 2020. They obtained a BFA from Concordia University and an MFA from OCAD U.