Temporal Displacement and the Memory of Soil

By Taryn Wiens

Changing human–soil relations require material, ethical and affective ecologies that thicken the dominant timescape with a range of relational rearrangements. In these relations of care, the present appears dense, thickened with a multiplicity of entangled and involved timelines, rather than compressed and subordinated to the linear achievement of future output.

–Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, “Making Time for Soil,”

Reading Site through Soil

What soil is depends on what you’re looking for. The US Department of Agriculture classifies soil according to its balance of clay, silt, loam, and organic matter to determine crop production potential; archeologists read soil as a cultural record-keeper, as a repository of past human life; geologists read soil as a material that once was rock (parent material) and one day will become rock again; ecologists read soil for its capacity to hold specific communities of non-human life. Soil is all of these, but not reducible to any of them. As both a record and generator of landscape processes and human activities, soil can be a guide for recognizing temporal cycles and ruptures of the past, intervening in present practices, and imagining a multitude of futures. As a bridge between social, ecological, and material aspects of site, thinking with soil can reveal entangled relations rooted in place—and our position within these relations.

By this logic, the discipline of landscape architecture should have a deep and varied consideration for soil as a time-based material and prioritize engagement with ongoing time-based land practices that are bound up in soil (like farming, gardening, land management, and cultural ritual). However, discourse like this exists mostly in theoretical studies of landscape and very rarely in design practice, where the linear process of design, culminating in a singular moment of construction, encourages one-time, human-driven interactions with soil (like earth moving, infrastructure building, and plant installation). (1) Engaging in both the study and practice of landscape architecture brought my awareness to this ideological rift and initiated a research interest in soil and its greater capacity as an ecological/social signifier and tool for change.

This inquiry is grounded in a wildlife refuge in the Klamath Basin on the border of Oregon and California, a few hours from my parents’ home. The area has been homeland to the Modoc people of the Klamath Tribes since before recorded history. Engineered by white settler politics and infrastructure, the basin is a contested site of racial tensions and environmental crises. Soil became the common thread in the research, a way to trace the entangled spatial, social, and temporal relations that make up this landscape and possibly inform more temporally diverse ways of practicing landscape architecture. As an act of tracing, the content of this research formed as it occurred. Many voices shaped the work through site visits, long conversations, and archival research.

I respectfully acknowledge this research is sited within the homeland of the Modoc people of the Klamath Tribes and recognize the unique and enduring relationship between Indigenous people and their traditional territories, as well as the ongoing dedication of the Klamath Tribes to the survival and wellbeing of their more-than-human relatives. It has been an honour to speak with and learn from members of the Tribes. (2) The research, writing, and graphics of this article were composed on unceded lands of the Modoc/Klamath, Central Kalapuya, and Monocan peoples.

Water Scarcity and Soil Temporality

Before 1905, a large area around what is now the Lower Klamath Wildlife Refuge held two separate drainage basins separated by Sheepy Ridge. To the east, in the Lost River Subbasin, Clear Lake fed the Lost River and drained into the aquifer beneath Tule Lake, which would grow or shrink with the seasonal water flows. To the west of the ridge, in the Lower Klamath Subbasin, the Klamath River fed a similarly dynamic seasonal system of small lakes and marshes that were constantly reconfiguring. Winter moisture and spring snowmelt overflowed the Klamath River and fed the seasonal water bodies. The swelling river flowed through soil and plants. The water brought plant growth, which created a filtration system; flooding would kill some plants, which decayed into rich peat soils and led to more growth; each sequential step supported the next. In the summer, water drained and continued its journey down the Klamath River to the ocean. Together these two seasonal marsh and lake systems covered more than 100 square miles and supported millions of birds migrating up and down the Pacific Flyway. (3) The Indigenous Modoc people of the Klamath Tribes have lived embedded in these systems since “time beyond memory,” as the Tribes describe it. (4) Their now-suppressed practices of fishing, harvesting and preparing food, setting fires, and cutting vegetation promote further richness in the landscape. Before white settlers arrived, these activities heavily shaped and were shaped by the landscape. For example, tule reeds were burned to encourage the growth of now scarce wocas, a yellow water lily whose roots are ground into a nutritious flour. In this process of burning and harvesting, the edges of the marshes were, in a way, gardened. (5) Indigenous cyclical human-plant-animal-material processes have always occurred here at multiple timescales.

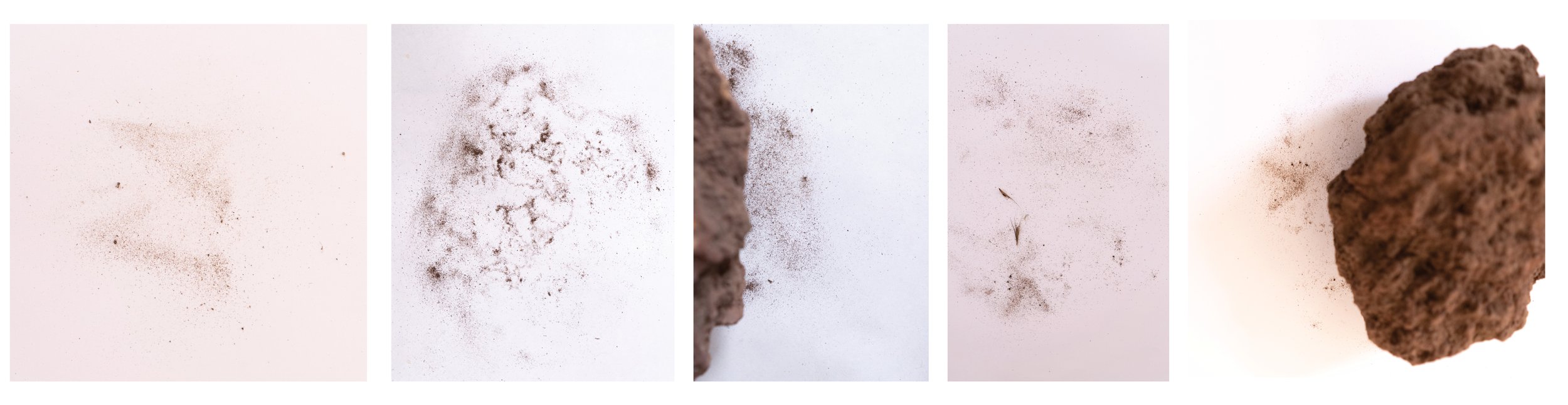

At the turn of the twentieth century, the US government forced Modoc people from their homelands and promised white homesteaders productive irrigated farmland in the marshes. Over the past 120 years, the US Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) has connected the two watersheds and entirely restructured the water flows with construction and maintenance of hundreds of miles of canals, massive pumps, dikes ten miles long, and thousands of water control structures. The two subbasins have become one in which water can be cycled around at will. The whole area is now the Lost River Subbasin and ultimately leads back to the Klamath River when it drains. The USBR created hundreds of “units,” as land managers and farmers call them, to provide scaled, productive land—areas bordered by dikes and canals that can be flooded or “dewatered” to precise levels and make for a curious, gridded satellite view. When the USBR cut off the Lower Klamath marshes from their river source in 1908, US President Theodore Roosevelt established the first waterfowl refuges in the United States in an attempt to save the key habitat for migratory waterfowl that had already begun to be destroyed. The draining revealed highly flammable non-productive dry peat, so while farming units were developed around Tule Lake and elsewhere in the basin, Lower Klamath burned and created massive dust storms. After 40 years, in the late 1940s, the USBR decided to “solve” this problem by pumping water from Tule Lake under Sheepy Ridge to reflood the dry and dusty former Lower Klamath marshes, then built canals, pumps, and control structures to drain that water across two dikes back to the Klamath River, in order to make the newly flooded land farmable. While the decisions to drain and flood and drain again were driven by the USBR’s mission to maximize agricultural output, some water still travels through refuge lands, where the infrastructure is used to produce habitat for migratory waterfowl. Areas outside refuge boundaries are privately farmed, either by farmer-owners or through annual leases to farmers on federal land managed by the USBR. Although significantly disrupted by settler colonialism, the Indigenous practices of the Modoc people are recorded in the deep soil underneath all of this, and some activities are still practiced by Tribal members in nearby areas on smaller scales. The memory of soil is powerful; even soil that’s been dry for decades will produce emergent marsh vegetation when flooded at the right time. The historic marshes and lakes can still be read in the moisture capacity of the soil.

Today the most pressing issue, according to both local residents and the national media, is that there is not enough water to support current land use: the complex ecological systems, cultural practices, and amount of active farmland cannot all survive in their current state with the variable and finite volume of annual rainfall and runoff. (6) This ongoing crisis, exacerbated by climate change and more frequent drought years, forces land managers, land stewards, and farmers into reactive stances and makes invisible all temporal relationships to the landscape other than the annual. “How much water will we get this year?” becomes the only question.

Current practices, although efficient in their primary goal of annual productivity (either of crops or bird habitat), produce a whole host of other problems. Among these are decreasing soil fertility, increasing soil salinity in areas that don’t receive regular water flow, nutrient-loaded water flowing back to the river without being filtered, increasing water temperatures in the rivers, dust storms from dried-out former marshes, reduction in the number of migratory birds that can be supported by this key stopover, increasing rates of botulism in birds due to low water flows, endangered fish, and loss of plants like wocas that are part of Indigenous ways of life. Although these problems have been identified, the water conflict has not left room to experiment with or advocate for management sequences that could change their trajectory. The refuge managers often don’t know they’ll be getting water until a day or two before it arrives, and it’s rarely enough.

To add another knot to an already knotty landscape, from 1942 to 1946, one of the ten Second World War incarceration camps where Japanese Americans were imprisoned was located at Tule Lake. (7) Although usually told as a separate history, incarceration is entangled with farming, colonization, wildlife refuges and Indigenous practices. At the edge of Tule Lake, the daily lives of incarcerated Japanese-American people during that time have been recorded in the same soil that holds the memory of earlier Indigenous practices. The trauma of incarceration has been recorded in the same soil as trauma of the Modoc people during violent skirmishes with white settlers in the late 1800s—the same site that white settlers named “Bloody Point.” Tule Lake incarceration camp was located here because the War Relocation Authority desired remote, workable farmland (the USBR helped determine where the camp would be located) (IMAGE 7 HERE). Japanese Americans laboured to extend irrigation and produce food not only for everyone living in the incarceration camp but for the larger “war effort.”These entanglements are not coincidental but stem from the process and logic of colonizing this area: moving water and moving people to “solve problems,” manufacturing both excess and scarcity, normalizing whiteness.

Tule Lake incarceration camp was also adjacent to refuge land. Japanese Americans would dig for shells in the drained lakebed and watch the birds overhead. The Second World War occurred before Lower Klamath was re-flooded, and Tule Lake incarcerees commonly remarked on the ever-present dust “seeping through the windows; blanketing furniture and floor with a coating of white. Dust. Dust. Dust.” (8) The camp was also adjacent to one of the most significant areas for Modoc petroglyphs, and incarcerated Japanese Americans painted Japanese characters next to the marks of the Modoc. (IMAGE 9 HERE) Some incarcerees made small gardens by their barracks using lava rock. One was a landscape architect who designed a rock garden around the camp’s main office. (IMAGE 10 HERE) The lava formation from which these rocks came, called Ktai' Tala by the Modoc people, is not only a deeply sacred place but also the seat of the Modoc War of 1872, where 60 Modoc warriors held off the US Army for many months, and where their annual relay run through their homelands culminates in a ceremony. Soil, geology, and archives reveal all of these siloed histories as deeply entangled.

Later in the twentieth century, the government finally recognized (but did not fully fulfill) the water rights of the Klamath Tribes and the water needs of the Klamath Tribes’ sacred, endangered, endemic fish species (c’waam and quapdo), which had been decimated by the USBR’s activities. Today’s water conflict stems from the fact that more water is promised or expected through a quilt of state and federal laws, designations, and agencies than exists. People are mired in legal battles over which land uses get priority. It’s clear that everybody is losing, but no one can find a way out of the gridlock. As of this writing, 2021 is set to be perhaps the worst drought year in memory.

To address the problems brought on by current management practices, land managers must expand and diversify the timescales they focus on. We must bring back displaced temporalities. Instead of looking at how much (agriculture, habitat, etc.) can be produced with the quantity of available water in a given year, I propose turning the focus to how practices with water are recorded in the soil, and at what timescales. (9) Focusing on soil as a cultural and ecological record can show that activities and attitudes that seem immutable in the current climate are relatively new; that the current practices can be changed because the material people stand on and eat from was made from different ways of being, not too long ago. It reveals material traces and the displaced temporalities of practices that are now invisible in the current annual-dominant landscape, except to the Indigenous people. Soil as a material holds the marks of trauma and transforms them through chemical and biological processes. Paying attention to this can be a way for communities to acknowledge and process violence in a way that also heals toward the future. Attending to the health and wellbeing of soil offers a means to shift values from maximum productivity to diversified timescales of relating in mutual care. This is not a solution, but a way of seeing, of peering through soil windows to socio-eco-geologic relations and expanded temporal awareness. Thinking with soil shifts the focus from finding band-aids for the crisis of immediate scarcity to imagine how things could be on a longer timescale—to see possibilities of transitioning current practices into something other than a future without fish, birds, or food: something other than the current trajectory of linear productivism.

A Place-based Listening Methodology

I initially learned about the Klamath Basin through secondary sources and maps, but triangulated those with extensive in-person interviews, site-visits, soil sampling, and photo archives to piece together a place-based history in the spaces between these sources. In-person conversations were necessary to understand how the problem of water scarcity manifests on the ground. Each conversation led to another: refuge staff connected me to a farmer, who put me in touch with an agronomist. Refuge staff also referred me to a fish scientist with the Klamath Tribes. Mutual friends led me to a Modoc artist and activist, and other acquaintances spoke with me about their experience as descendants of people who had been forced to live and labour in Second World War incarceration camps. In every conversation I came to share each person’s concerns, and to understand the goals of their land practices and their limitations. Although this methodology was full of rabbit-holes, and not especially precise, it was important to me to make a real attempt to understand the perspectives of the people and non-humans that this place matters most to; to understand what is at stake and to try to make the research relevant to them, and not just to an academic audience. Ultimately these conversations were hopeful: each person I spoke to wants to find a way to co-exist and thrive together. It appears that the difficult part is imagining what that would even look like, or how to work toward it in the current conditions — conditions that include the increasingly racist and polarizing far-right political activity of much of rural America.

Changing Practices to Change Infrastructure

During site visits I sat in on a staff meeting for the refuges, interviewed the refuges’ manager and wildlife biologist (one office manages both refuges and three more in the area), and rode around for three hours in a maintenance truck with the head of operations. Through these experiences I witnessed the immense place-specific knowledge and skills that refuge staff employ to support 50 percent of the birds that migrate in the Pacific flyway during nesting, spring and fall migration, and wintering. They accomplish this with a tiny fraction of the historically available water by cycling it strategically through different units.

Infrastructure, as well as expertise, allows this efficiency. I was surprised to find that wildlife habitat on the refuges is, in essence, farmed. Flooding and dewatering of units are the main operations, while burning and discing are used to control undesired plants. Farmers use these same techniques to produce wheat, barley, and potatoes. While farmers plant their crops, on the refuges the native plants that feed birds emerge when the soil has the right moisture content. Farmers harvest their crops with machines, while on the refuges, plants are “harvested” by flooding units for two to three days during migration so birds can access the food. The water crisis can make farmers and the refuges appear in total opposition, but the land management practices are the same, and land-use states are interchangeable from year to year. Although the majority of farmland is spatially fixed, a seasonal wetland unit could theoretically become a wheat farm, be hayed and grazed the following year, and become a continuous wetland again the year after that. Already the refuge managers and farmers take advantage of this on a small scale with the “Walking Wetland” program: farmers flood their fields for a few consecutive years in exchange for access to wheat farming leases on the refuges. They leave every fourth row of their crop as standing grain that feeds waterfowl during fall migration. The Klamath Tribes use the refuges’ infrastructure to rear c’waam and quapdo in small ponds. There is a desire among the refuges, the Tribes, and many farmers to find common ground where interests overlap. The infrastructure supports the current collaborations and would be essential to expanding them.

Although the dikes, canals, pumps, and units were established with a productivist aim, they only remain in service to those goals through day-to-day practices and maintenance. Infrastructure is not complete or incomplete, it is an open-ended process. (10) The same physical infrastructure, operated with different goals and a greater diversity of timescales in mind, would produce a vastly different landscape

It’s tempting to fixate on infrastructure as the most visible physical change in the landscape, but that misses the point. Infrastructure doesn’t carry much inherent value: it can enable terrible and destructive practices or enable generative and healing ones. Infrastructure is mutable and must constantly be reinforced. The choices of how to maintain it, how to use it, when to expand it, and when to remove it or intentionally let all or part of it decay are ongoing choices. Soil is a useful lens for making these decisions because it absorbs and records the day-to-day practices that happen with and around the infrastructure, recording the form of the infrastructure along with many other geological, hydrological, ecological, and agricultural forces that compose the ground. (11) What if these choices prioritized the health of the soil? What if the infrastructure was employed to build upon and nurture the specific soil underneath each unit instead of trying to squeeze maximum production of crops or habitat from it until it reaches an imbalance—of nutrients, salinity, or toxic bacteria—that prevents it from producing?

Could scientists, farmers, and the Klamath Tribes decide together, for each unit, what they want the soil to be in one hundred years and use that goal to drive management decisions, with land use mutable from year to year in proactive (not reactive) management?

There are a lot of bureaucratic and economic barriers to this idea currently, and of course other important aspects of management like water flows needed for fish at particular times, but thinking about management as a method of building soil on long timescales could potentially change the collective imagination and expectations around this land. It’s a step toward reframing the current problems from a question of who must make sacrifices (since sacrifices are already being made on all fronts and will continue to increase) to a question of what people expect of the landscape, how they relate to it, and what futures they imagine for it.

I’m not advocating throwing a wrench in the current system, because to suddenly stop all current practices would be even more harmful than their continuation. The idea that a singular constructing (or deconstructing) act could solve the problems is exactly the type of thinking that drove the USBR’s series of mistakes, which is of a kind with the “before” and “after” structure of standard landscape architectural practice. Instead, change must come with and through the people making day-to-day decisions on the land, with respect for their place-based knowledge. Within the cyclical nature of existing landscape practices, I propose a greater attention to learning through soil and allowing for ebbs and flows on many timescales simultaneously, with particular elevation of Indigenous land practices and knowledge that have been suppressed. Attending to the soil commons might replace the current illusion of perpetual linear growth that shades out all other concepts of time. Changing land practices would slowly shape the infrastructure to fit the environment, not the other way around.

Thinking with soil beyond its immediate capacity for commodity production can be a powerful tool for tracing threads through knotty landscapes. It weaves together social and ecological contexts, past, present, and future. Soil is a tactile material but never fully visible—and never fully static. It is defined through its relations and always changing. These qualities make soil a good vessel for place-based imagination. As people continue to face crises and challenges too big to fully comprehend, soil can be an ever-present guide—as long as humans stop treating it like a resource to be mined and start treating it like an intimate relation with an infinitely long and varied existence.

The following two “Frames” explore how interactions may be facilitated that put different people of the Klamath Basin in conversation with one another and with soil, speculating paths forward that prioritize nuanced spatiotemporal relations and balance over annual productivity. (12)

Frame I

Current Management Practices / Design for a Living Soil Library

The Soil Library frame establishes a finer scale within the existing infrastructure: an existing 384-acre unit at the intersection of the various water sources (Tule Lake through Sheepy Ridge, farm runoff, Klamath River water) and on the main road through the refuges is divided into twenty-four units of sixteen acres each. Here the Klamath Tribes, the wildlife refuge management, and the agricultural extension/USBR each control eight units to freely experiment with different management sequences. The Tribes dig one unit deeper and keep it permanently inundated as C'waam habitat with underwater viewports, and in another unit they experiment with tule, Wocus, and burning in a seasonal wetland. Other units are C'waam rearing areas and a marsh plant nursery. The refuge scientists tinker with timing the water supply to encourage emergent bird food while controlling invasive vegetation without the discing that rips up the soil. On the main refuges scientists haven’t been able to test water timing with any control because they are only notified that the water pump will be turned on a day or two in advance. So even though they could design the timing of each unit around ecological needs, there would be no way to ensure they would receive water at the right time. With smaller units that require much less water to flood and access to three possible water sources instead of two, timing and quantities of water can be worked out ahead of the season. The agronomists try to figure out how many years of continuous wetland would enable a unit to be farmed for a year without any irrigation, and in a few other units test how well different wetland compositions filter crop runoff before returning it to the river.

Co-produced relational knowledge formed over time lets groups negotiate beyond “this much water or that much water.” More mutually beneficial temporal practices emerge. A new visitor centre holds an even smaller rammed earth grid of twenty-four 12 x 12-foot units that mirrors the larger grid. Each year soil samples from the larger corresponding units are spread into the rammed earth units, and visitors can learn about the different practices and see the resulting different soils and emergent vegetation. The display plots also leave room for a soil imaginary—to speculate on what is happening below ground and over time through affective attention. People cannot see all of the layers of soil but they can watch the display plots change over time, take cores, and envision together what is below. To make soil fully visible is to de-place it, to break its relationality, and for that reason it always exists somewhere between what we know and what we imagine.

Out of this, over some years and with government support, a cooperative public Klamath Resiliency Collective is formed. Witnessing Indigenous knowledge through their ways of tending to the soil side by side, year after year leads farmers and scientists to support Tribal leadership of the collective. The collective buys farmland from farmers with declining yields and from farmers’ children who want to move away from the Klamath Basin. The USBR transfers some of the land it owns and currently leases to farmers to the collective until the amount of land being farmed in any given year is not more than the ecosystems can hold. The Klamath Resiliency Collective petitions to dismantle some infrastructure near where the water from wetlands and farmlands drains back into the Klamath river and establish a permanent wetland that mimics pre-USBR processes. All runoff is filtered through this wetland as a last stop before going back to the river. Nutrient loads, sediment, and temperature decrease in the river and the fish populations start to rebound. Previously dusty soil regenerates with layers of decomposing marsh vegetation. In fall, the sky is dark with birds.

Frame II: Existing Cultural Practices / Design for a Speculative Soil Garden

Twenty miles down the road from the Soil Library, the soil of Tule Lake was farmed by Japanese American prisoners during the Second World War. After the war that land was given to white farmers by lottery. Their sons and daughters still live and work here, farming potatoes in the rich and productive former lakebed. / Each year in the spring these farmers walk to the soil garden near the incarceration camp memorial site and plant potatoes by hand and water them deeply. A couple of months later, when the plants are six inches tall, they return to scoop soil and mound each row of potatoes; the same process that they perform on their own farms, but intimate, by hand.

Every two years for four days in July survivors of internment and their families make a pilgrimage to the ground where the Tule Lake Internment Center used to

be to hike to the top of Castle Rock and remember together. / The pilgrims visit

the soil garden together and fling daikon radish seeds between plots of epos and camas bulbs and remember how their families of non-farmers were forced to plant and irrigate and harvest in this soil in order to support the war effort of a country that didn’t recognize them as full citizens. The pilgrims leave small objects of wood and stone and paper that remind them of their families and the trauma they endured here.

Every year for two days in early October, Modoc tribal members run a relay over 150 miles from Upper Klamath Lake to the Lava Beds as a way of reasserting their connection to their homelands. / When they near the end of the relay, they gather at the soil garden, pull the big daikon radishes out of the soil, and harvest the potatoes. They also harvest their traditional epos and camas roots, return the first of the harvest to the adjacent clockwise plot and speak words that connect back to their ancestors, clean the bulbs over the soil and replant the small ones. Where epos have been harvested, and where potatoes will be planted in the spring, they set a small fire to clear the ground, add compost, small rocks, and the objects of memory left by the pilgrimage. Over time these rocks and objects break down, materially and metaphorically processed, combining with organic matter to become new soil. Winter rains prepare the soil garden for next year’s planting.

These speculative futures produce more questions: Could soil lead residents to active and ongoing relations of care that generate and reveal a thickened and entangled timescape? Can soil be a mediator and medium for processing trauma? How do we perform and value land practices centred around social healing and soil building? What does decolonization of a thoroughly colonized landscape look like?

In the context of landscape design, they bring up questions like: What does it mean to “construct” a site with ongoing practices? Can we design less “fixed” things and design more for relationships between different human and non-human agents? Where does designing fewer “solutions” and more possibilities (and impossibilities) take us? How can we design with ongoing responsiveness to changing conditions? I look forward to continuing to sift through these questions and to ground them in different soils.

Endnotes

(1) There are of course exceptions, like the EMF’s Girona’s Shores project, which is continuously implemented entirely in the landscape with the parks department maintenance staff of the city of Girona. Occasionally contracts do allow for maintenance/management plans as part of the design scope, but as designers rarely have a hand in managing or maintaining landscapes before or after the window of design, it’s difficult for them to account for all potential responses to a constantly changing landscape in a one-time plan deliverable. In academia however, this concept of an ongoing landscape is widely accepted and can be found in different manifestations across social theory, anthropology, environmental studies, Indigenous studies, and landscape theory. Anthropologist Tim Ingold makes a strong case for this in his idea of the “taskscape” in his 1993 essay “The Temporality of the Landscape” (World Archaeology 25, no. 2 (1993): 152-74). Landscape scholar Julian Raxworthy devotes an entire book to discussing this idea and its tension with landscape architecture in Overgrown: Practices Between Landscape Architecture and Gardening (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2019). Donna Haraway speaks about this concept as “becoming with” in Staying with the trouble: making kin in the Chthulucene (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

(2) Knowledge of some current Modoc cultural practices came from conversations with Modoc artist and activist Ka’ila Farrel-Smith. Awareness around current efforts to save their sacred fish came from conversations with Alex Gonyaw, senior fisheries biologist for The Klamath Tribes.

(3)If you are interested in supporting the Klamath Tribes as they work to save the endangered c'waam and koptu fish and steward the larger ecosystems of their homelands, please consider donating to the newly established Ambo Fund. More information at https://www.seedingjustice.org/the-ambo-fund-water-for-the-klamath/.

(4) The Pacific Flyway is a major north-south flyway for migratory birds in the Americas, especially waterfowl, and extends from Alaska to Patagonia.

(5) “Klamath Tribes History,” Klamath Tribes, accessed June 1, 2021, https://klamathtribes.org/history.

(6) My understanding of traditional Modoc land management primarily came from Douglas Deur’s article “‘A Caretaker Responsibility’: Revisiting Klamath and Modoc Traditions of Plant Community Management,” Journal of Ethnobiology 29, no. 2 (December 2009): 296–322.

(7) There are a plethora of articles and books about the water crisis of the Klamath Project. As a recent example, see Mike Baker, “Amid Historic Drought, a New Water War in the West,” The New York Times, June 1, 2021.

(8) While the War Relocation Authority euphemized incarceration camps as “relocation centers” and historical accounts often label them “internment camps,” I have taken cues from the Tule Lake Committee and Japanese American Citizens League to use language that more accurately reflects the history. National JACL Power of Words II Committee, Power of Words Handbook: A Guide to Language about Japanese Americans in World War II (April 27, 2013, Revised August, 2020).

(9) Arthur T. Morimitsu, “Fleeting Impressions,” The Tulean Dispatch. "A Tule Lake Interlude: 1st Anniversary, May 27, 1942–43," in the Harold S. Jacoby Nisei Collection of the Online Archive of California, 1943, 56.

(10) This approach is greatly indebted to Maria Puig de la Bellacasa and her essays “Making Time for Soil: Technoscientific Futurity and the Pace of Care” and “Re-Animating Soils: Transforming Human–Soil Affections through Science, Culture and Community,” The Sociological Review 67, no. 2 (March 1, 2019): 391–407.

(11) Some environmentalists have proposed removing the infrastructure on the refuge to re-introduce more “natural” processes, but because the water sources to the refuge are still tightly controlled, this would only make the ability to move water less precise and would inhibit the current efficiency to the point of ecological disaster. The infrastructure is not necessarily the problem: it is what the infrastructure is used to do (to produce maximum annual outputs of food and habitat) that creates the current conditions. For a great discussion of infrastructure as an open-ended process and other social and political dimensions of infrastructure, see Nikhil Anand, et al., eds., The Promise of Infrastructure (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), particularly Part 1, on “Time.”

(12) As Manuel Tironi et al. put it, contemporary social theories “locate soils as generated by multifarious practices, apparatuses, and modes of attention” and they “take soils as generating publics, politics, and relations.” They go on to say that many Indigenous epistemologies and ontologies precede these ideas and reference Indigenous studies and sociology scholar Vanessa Watts in saying that “our truth . . . in a majority of Indigenous societies, conceives that we (humans) are made from the land; our flesh is literally an extension of soil.” “Soil Theories: Relational, Decolonial, Inhuman,” in Thinking with Soils: Material Politics and Social Theory, eds. Juan Francisco Salazar, Céline Granjou, Matthew Kearnes, Anna Krzywoszynska, and Manuel Tironi (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020), 17, 29.

(13) For more on speculative design as an approach, see Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2013). My approach also draws from Anna Tsing’s idea of “friction”—specifically the way she advocates for “attention to historical contingency, unexpected conjuncture, and the ways that contact across difference can produce new agendas” in “On Nonscalability: The Living World Is Not Amenable to Precision-Nested Scales,” Common Knowledge 18, no. 3 (August 1, 2012): 505–24. .

Bio

Taryn Wiens is a landscape designer at Nelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects. Her research is focused on the possibilities of time-based land practices as a core medium of landscape design. She received her MLA at the University of Virginia in 2020, where she served as an editor of UVA’s design research journal LUNCH. This research has been funded by UVA’s Benjamin C. Howland Traveling Fellowship.