The Rules of the Road: Canfield Drive as a Site of Architectural Discrimination

By Biko Mandela Gray and Linda Zhang

We often perceive roads as neutral. We’re made to see them this way. Conversely, they’re built this way. Roads appear only to disappear; the concrete, asphalt, and yellow or white lines lie there, allegedly available to anyone. And when we use them, they vanish from view.

This disappearing act is important. It’s necessary. Roads are public, after all; they’re available to everyone. We get in the car, turn the key, press down the gas. We move along the lines. In driving, we assume the road has nothing to do with who and what we are outside of our identities as travelers.

But take a closer look. Pay attention. Roads are far from neutral. They tell you what to do; they direct and guide the flow of traffic. Roads have rules, and if you don’t follow them—if you run a red light or blow through a stop sign, if you go too fast or if you fail to signal—the road will turn on you. Lights will flash. And if you are not the right kind of person, things could escalate. They might get violent. You could be imprisoned or killed—or both.

This is what happened to Sandra Bland. When Bland, a black female civilian, expressed her irritation of being pulled over on the road to Brian Encinia, a male officer, she disrupted the normative flows of history, race, gender, and state-sanctioned power. Though Brian Encinia’s stated ethnicity is Mexican, his actions invoke a history of relations between white men and black women. What might have been an ordinary traffic stop became a scene of profound violence. She was brutalized, beaten, and then imprisoned. She would die in jail three days later. All because she didn’t follow the rules of the road.

Roads direct more than traffic. As acts of public architecture, they are enmeshed in normative structures. They don’t simply tell us how we should normally drive; they also make distinctions between those who should be on the road and those who should not. If you’re not driving—or at least not in a vehicle—the normativity of the road becomes all the more apparent. If a non-driver/non-rider gets on the road, they are rendered suspicious, criminal. In their discriminatory function, roads enable officers of the state to determine who and what is criminal, who and what is deemed suspicious. The rules of the road do more than tell us how to drive; they do more than keep us safe. They tell us who should or shouldn’t be here and how.

Sandra Bland was accosted for failing to signal, but Michael Brown was stopped for walking. He was near his home. He was close to his destination. There weren’t many cars around. The road wasn’t being used heavily. So, he walked. And he walked as a Black man, a large one. In walking, Michael Brown disrupted the normativity of the road. He would die for it, and his body would lie in the streets for four and half hours after he was killed. Don’t be fooled; roads can kill.

In Michael Brown’s case, he was the traffic; he was disrupting the normative flow of the road. “Traffic”—be it vehicular, ambulatory, social, or political—is produced when something flows against the established (historic, normative, socio-cultural) direction. Regardless of the magnitude of the vector, it is its orientation that contributes to the disruption.

Contestations:

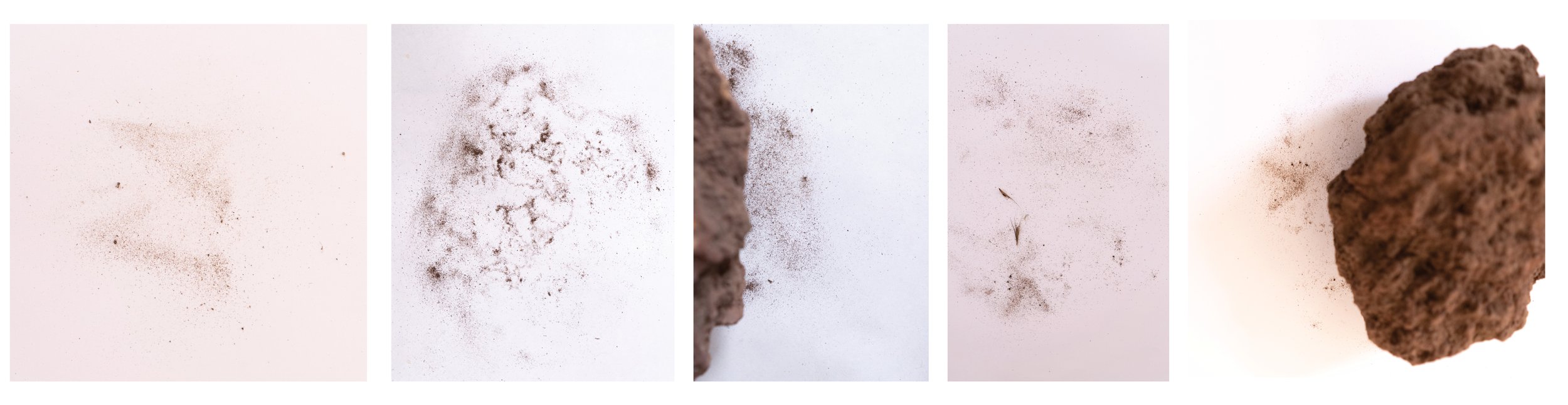

The Phenomenology of the Road is a ceramic quilt made from indexical 3D scans of roads that are sites of confrontations between law enforcement officers and Black civilians. We began by directly 3D scanning the roads and then used the process of ceramic slipcasting to investigate the events and conflicting memories surrounding these confrontations. While each cast was taken directly from the 3D scan, we used the casting process to embed aspects of the site which transpired over time—intangible aspects which cannot be captured by the static 3D scans. Through this thinking-through-making process, a distance is created between the object of the road (indexed by the 3D scan) and the phenomenology of the road (indexed through the slipcasting process). The time-based process of casting and the purportedly objective 3D scan of the site offer a starting point to understand the relationships and entanglements which transpired along the Phenomenology of the Road.

This visual essay takes one set of ceramic tiles from the design-research and teaching collaboration between Linda Zhang and Biko Mandela Gray to demonstrate how the architecture of the road is not neutral, how the normativity of the road can turn people into traffic, and how this transmutation of people into traffic can produce violently unresolved and irresolvable encounters. The media frames these encounters as contestations—between blue lives and Black ones, between those who support police and those who stand on the side of the lives lost—but such framings inevitably dissimulate the brutality of discrimination itself. What never gets asked, what never gets questioned, are the rules of the road—those rules that place people under suspicion and therefore occasion the encounters in the first place.

We chose Canfield Drive, the site where Michael Brown was murdered, to expose this contestation. We will not recount this story in its fullness. It’s too well-known and too brutal to recite. But we wanted to stay at Canfield Drive to see what the road opened up. We recognized that, although the space is contested, this very contestation obscures the violence. A contest between blue and Black lives covers over the originary violence of discrimination—a violence that is made possible by the road itself.

Tarnishing:

In these tiles, our students Amelia Gan and Sabrina Logrono call this contestation “tarnishing identity”; drawing from the phenomenology of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, they highlight how the road does much more than condition travel. It can and will leave broken lives and legacies in its wake. “Due to the different interpretations of what happened on August 9, 2014,” they explain, “Mike Brown's identity has been tarnished. Different versions of Mike Brown exist in the minds of the public: some see him as a thief while others see him as an innocent man.” (1) Tarnishing—which can be traced to the Old High German tarnjan, which means to conceal or hide, or the Old French terniss, which means to dull the luster or brightness of, make dim—is an act that obscures. And it obscures through time, acting on something, someone, or someplace, altering things to be less bright, less sharp, less clear.

On Canfield Drive, each witness account obscures the last. Each one tarnishing the other, and over time, making more dim, more contested, and more obscured what events really transpired. On Canfield Drive, this tarnishing also happens literally: in the materiality of the road itself. Michael Brown’s body lay in the middle of the road, interrupting the yellow lines of the road that, normatively, should have split the road between oncoming and forward-moving traffic. And as his corpse lay there, on that road, his blood mixed with the asphalt of Canfield Drive; Michael Brown’s DNA is embedded in the road itself; as each retelling of this story moves us further away from Michael Brown’s identity, each car, each footprint that passes along Canfield Drive also conceals Michael Brown’s identity even further.

Taking this insight and running with it, our students overlaid the site with “a fingerprint, a marker of identity, as our ground zero in this project.” (2)

By superimposing a fingerprint onto the site itself, the road takes on a fleshly over- and undertone. As Merleau-Ponty intimates, flesh is not a thing unto itself but a material condition for physical encounters. The road, then, is enfleshed; blood-mixed asphalt exposes Canfield drive as a site of fleshy and fleshly encounter.

The colours matter here. “The pink colour illustrates the flesh,” our students explain. “It is the colour we begin with in every cast; it encompasses all.” (3) Turning the inside out, drawing from the idea that internally, our organs are flowing with blood and bone, sinew and muscle, we find ourselves experiencing the fleshly nature of the road. It is Brown in his fleshiness that is primary.

But what about the aquamarine? Here’s where the beginning of the tarnishing comes in. If Michael Brown’s identity is embedded in the materiality of the road, then the aquamarine announces a disruption—an interruption—in the fleshly and fleshy movements of Michael Brown’s walking: That interruption was Wilson and his homicidal actions. In other words, Michael Brown’s identity is enmeshed with the road because of an interruption by a putatively “blue life” whose worth overtakes and disturbs the Black life walking in the street. The aquamarine is layered with more blue layers, until we have something like a clearer, more cobalt blue showing itself in the tiles.

Wilson’s interruption isn’t simply manifested through his presence, though. It also shows itself through the bullets that pierced Michael Brown’s flesh. Hence the lines in the original design: “The bullet paths ruin Michael Brown’s identity which, in our original tile mold, is portrayed by a fingerprint embedded in the site.” (4) The lines cut through the fingerprint, interrupting its coherence.

So we have Wilson’s interruptions. But there are more: as the event sediments in national memories, we are confronted with the fact that time itself obscures Michael Brown’s identity even further. Here’s where the tarnishing happens: as slipcast is carved away, the original design becomes more and more obscure: the fingerprint falls away and what we have is the residue of an encounter—one whose coherence is no longer readily perceptible.

The act of carving both settles and clears. The initial tile is not flat, it is shaped and formed by the topography of the site, the ridges of a fingerprint, and even the physical acts of piercing during the casting process. As the tiles are carved into flat and normative architectural tiles, these events are settled into a flat plane becoming more obscure. But, at the same time they also produce a new kind of visibility through colour itself. Like geological excavation, the layers of colour give visibility to time and processes that happened through time. Indices from the 3D-scanned site along with its events are both obscured and yet brought to the surface through the same act of carving.

The more the tiles are carved, the less we are able to perceive Michael Brown (and by extension, Wilson). What we’re left with is an eerie feeling that something happened; pink and blue intermingle to expose the failure of national memory. Michael Brown is neither victim nor aggressor, but lost somewhere between the two. And Wilson is neither murderer nor officer, but instead an eerie blue disruption in a field of pink. This, this, is how Canfield Drive is remembered in the U.S. national consciousness: an unresolved and irresolvable tension that problematically equivocates on the life-and-death stakes of this encounter.

Impasse:

The flesh—of the street, of Michael Brown—is interrupted and, as such, it folds back over and into this interruption, leaving what Hortense Spillers might call a “hieroglyphics of the flesh,” where all we have are indecipherable markings. “After excavation,” Gan and Logrono write, “each one of the differing tiles demonstrates the tension [of conflicting witness accounts] at different periods of time and from different points of view.” Rather than act as a progression, each tile embodies a . . . folding back, reversibility, and dehiscence of the flesh.” (5) There is no resolution. And in these tiles derived from and also departed from the site, Michael Brown’s identity is obscured, upended, and lost. In a word, it is tarnished. All we have left is the hieroglyphic residue of a brutal encounter, an encounter that continues to produce an endless number of interpretations.

When arranged together, the tiles announce the interruption, disruption, and tarnishing of Michael Brown’s identity. Michael Brown isn’t readily perceptible anymore, save in the pink horizon enfolding and flowing through the blue markings. All of this announces that we know Michael Brown was there, but we aren’t sure about who he was.

And this is the point: uncertainty. When placed together, the tiles do not allow the eye to settle; there is no symmetric point that will focus one’s attention on one specific tile or set of tiles. As they are quilted together, the pattern that unfolds is iterative; the repetition destabilizes the eye’s desire for order, mirroring the unresolved and irresolvable tension present at that site. One cannot see properly. And in this improper seeing, one is unable to remember properly.

This uncertainty has troubled any possibility of a memorial for Michael Brown. A makeshift Michael Brown memorial, replete with stuffed animals, flowers, and cards, was erected—and then promptly destroyed by an “accidental” fire. Nearby, a tree was planted as a living memorial and promptly—within twenty-four hours—destroyed, this time stolen along with its plaque. The tension remains. And in the end, Michael Brown is lost.

The Brown family removed the block of asphalt where Michael Brown’s blood was. They carved it out. They did so in an attempt to use the asphalt as his headstone. Perhaps they did it because this piece of asphalt was now enmeshed with his blood, his life matter. Perhaps they did it to try and overcome the tarnishing of his identity. Yet, the asphalt was too crumbly, and it couldn’t be used. It couldn’t be used to memorialize him. In the end, we are left with an absence in the road. A new layer of asphalt obscures the site where Michael Brown once lay for four-and-a-half hours after he was killed. It obscures the yellow lines which ought to separate the road. Just like each new iterative cast, it obscures the events we won’t (and can’t) ever fully know.

In obscuring the site and the events which transpired, the tiles reveal the normativity of the road. They announce the ways in which roads tells us who is a legitimate traveler as well as what legitimate travel should be. And when that happens, the road can haunt us; it can become a death marker. It can, as the final image intimates, become a site where stasis (which is to say death), not movement (which is to say life), reigns supreme. The tiles are a reminder that although we cannot perceive affective flows until they are disrupted, every space is charged.

Endnotes

1 Amelia Gan and Sabrina Logrono, “Tarnishing Identity” (Unpublished Manuscript, 2018), 1.

2 Ibid, 1.

3 Ibid, 1.

4 Ibid, 1.

5 Ibid, 1.

Bio

Biko Mandela Gray is an assistant professor of religion at Syracuse University. His research areas include continental philosophy, history of African American religions, and affect theory. He is currently working on a book that explores the connection between race, matter and embodiment, religion, and subjectivity through the lens of the "Black Lives Matter" movement.

Linda Zhang is a registered architect, licensed advanced drone pilot, and artist. She is a principal and co-founder at Studio Pararaum and assistant professor at Toronto Metropolitan University, The Creative School. Her design-research explores memory, cultural heritage, and identity as they are indexically embodied through emergent technologies, matter, and material processes. She is the 2022 Artist-in-Residence at the EKWC, the 2017–2018 Boghosian Fellow at Syracuse University SoA, and a 2017 Fellow at the Berlin Center for Art and Urbanistics as well as the recipient of the 2020 Toronto Excellence Award.