Murder of Crows

A written and drawn response to “Responsibility of Nothingness”

By Jishnu Bandyopadhyay

My uncle stands on the last step of the ghat, the murky water slapping against his ankles. The sky above is every colour but blue. Even though I have always seen him balding, I have never seen him without his French cut. The lack of his neatly groomed beard and substantial wisps of hair makes his silhouette almost unrecognizable. He fights against the wind to manage his rare attire, an ivory white dhoti. It’s a lazy evening, as evenings in Kolkata usually are. The impatient summer breeze brings a drowsy desire to snuggle up. For people who live in a riverine city, we barely come to the river; we have forgotten to make the time. Even today, it is not entirely by choice.

Another car drives up the street that runs by the Ganges. A woman not much younger than my uncle walks out of the driver’s seat. Her sari, the exact same colour as my uncle’s dhoti—they might have been cut from the same cloth. My brother brings out a sack from our car, quite carefully, as does the lady in white. My uncle gestures to take the contents out. Two folded banana-leaf packets are laid open on cement walls that line the shore. My uncle whispers, “They were made of bare bricks when I was young,” mostly to himself. The leaves contain two very different feasts, each meal curated with the favourites of the dead ancestors, who come back as crows once every year. One leaf reveals a sizable portion of shukto, sticky rice, and some potatoes and pointed gourd cooked with poppy seeds. The other has some fluffy, deep-fried luchi, aloor dom, and some ghonto made with bottle gourd. The sweets are a whole other deal.

When I was much younger my grandmother told me about how crows are the quintessential link between the worlds of the dead and the living; ancestors, it is said, visit the living in the form of a crow. After loved ones die, it is believed, every year on the date of their passing, they come

back as ravens to feast on their favourite food. Except this time there

are no crows.

We stand under the golden light of the setting sun as two other vehicles pull up. A rickshaw and a WagonR. Soon the riverbank is lined with meals. Incense smoke and garlands of jasmine, marigold, and rose dress up the drab colonial riverbank in no time. In the distance, words of prayer can be heard from the mosque, saving us all from a deafening silence. If you listen closely, there are so many sounds that make the place up, more so because they all render themselves into a unified background track. Everyone disperses a little bit, in hopes that the crows will feel more safe to come and peck at the food. A few minutes pass that feel like hours. I struggle to recollect the last time I was in a room with my uncle and no one spoke. The silence of strangers with a common thread of death linking their presence can be a powerful thing. A deadly force that can deem the need for words redundant.

“The crows are all dead!” someone mumbles with a sigh and breaks the engulfing loop. The lady in white looks at her watch, the little boy in white tugs at his nanny’s kameez with impatience. When the birds come, everybody has made themselves comfortable on various steps leading down to the river. The tangy smell of spices, flowers, and incense

have now taken over the sweet riverine breeze. Not one, not two, but

a large murder of crows gather around the decoded buffet. We linger for a little longer.

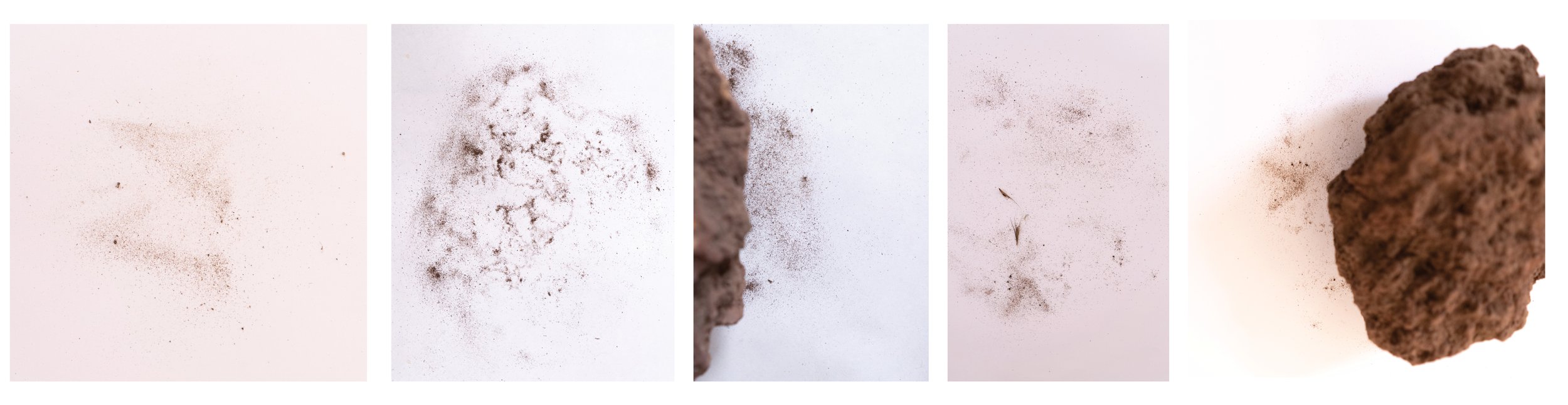

When we get back into the car, we still don’t speak. As the engine riles up I pull out my sketchbook. There are more crows on the bank now than there will ever be, all our ancestors reaching for their favourite meal yet another time. It’s almost as if the car doesn’t move, but the city does. Street lights and table lamps start to bejewel the landscape, rescuing it from drowning into an ocean of black. The sky projects beams onto the shiny parts of the town, holding witness to the sun that weakly slips behind the horizon. The tall glass buildings of the future somehow perfectly complement the ancient brick-and-mortar relics of a glorious past. I start sketching what I think looks like a crow skull. I wouldn’t know, I have never seen a dead crow in my life.

Bio

Jishnu Bandyopadhyay is the Creative Features Editor at Harper's Bazaar India. Their work focuses on fashion, and culture, through words, images, and illustrations. At 24 years old, Jishnu has contributed to and created for Architectural Digest, Condé Nast Traveller, Disney, GQ, Instagram, Them, UNICEF, and Vogue.