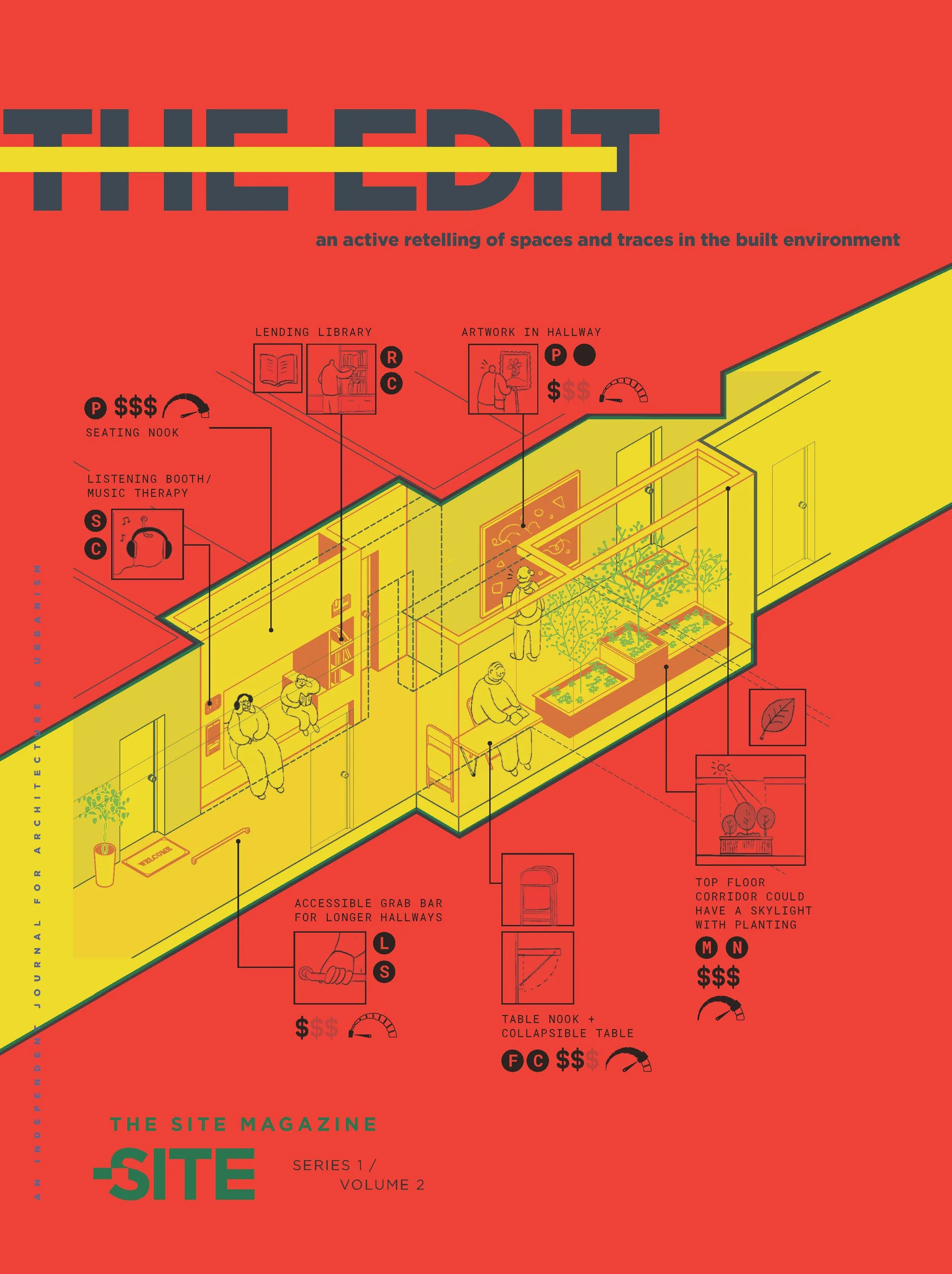

The Edit

By Amrit Phull

Language is a fluid and formidable technology. Manuscripts, letters, and decrees are decorated soldiers in the battle for discursive control. They pour from the heart of every conquest of Western empire building—the relentless project of scripting, deleting, and rewriting those parts of the world that did not place Europe at their centre. With or without our consent, colonial texts and imperial narratives of power scaffold how we describe, understand, and shape the world today. They are a large part of the foundation upon which we make sense of things, and they have always served a dual purpose: to justify some ideas, others needed to be “whited-out”—or erased and rewritten. This synchronous process of creation and negation (or editing) creates the milieu within which we score our own beliefs.

Editing is a human exercise in representation, something we all do in order to craft a perceived, ideal outcome. We edit our thoughts before speaking them aloud, just as we edit our digital profiles, social networks, and physical environments to reflect our needs and aspirations. Cities are in a continual state of erasure and reconstruction; nations are built upon places and peoples renamed, restructured, or removed. History is renegotiated and reforged in aeternum. At any scale and in any moment, we are mutually enmeshed in the constant, complex process of the edit.

Each passage and page of this publication is the result of a careful curatorial effort made through decisions about what gets to be included, how it is represented, and what is left out—so too with all written-and-read materials. And all editors know that good editing—the best editing—is meant to be “invisible” to obscure earlier drafts and ideas, to rewrite reality anew. So how do we confront the edit? How do we locate and restore what has been rendered invisible? And what might we learn from the early drafts, the original mock-ups, and decommissioned visions of our world?

Our contemporary language puts an emphasis on reversing oppressive edits (as in to decolonize, dismantle, defund, and so on.) But the historical and structural forces of colonialism, capitalism, and White supremacy have prompted irreversible, unerasable effects and affects that cannot simply be “whited out.” Bullets cannot be “un-shot,” communities cannot be “un-displaced,” nor can statues be “un-cast." The prefixes we use to reverse-edit are not there to suggest that the solution is to undo, forget, or rewind. These few letters instead create a radical space to write new ideas, norms, discourses, and practices into existence. These prefixes are a proclamation to redefine terms on our terms: an edit to end the tyranny of misrepresentation and oppression.

This issue situates itself within the space of the edit, in the gaps between what takes place, what is recorded, what we come to understand through the sedimented records of our reality. It invites a move towards new and different frames of rethinking and redoing. How might we uncover the complex, hidden iterations beneath the final inking? What will we find behind the backspace? Will we reveal truths and tools to overcome the pervasive burdens of a monolithic, heteronormative, Eurocentric coding, or will we need to script new ones? What needs to be written out in order to return what was and could have been, to move towards a communal future where we embrace our unbounded, unabridged, and unscripted selves? This issue explores the conditions of possibility that await us when we encounter, resist, and reimagine the edit.